You are currently browsing the category archive for the ‘politics’ category.

The Judaism I was taught regards trees as a particularly beautiful and sacred part of creation. It is a mitzvah to plant them. Given their slow growth and long lifespans, they are a gift to the future. Humans’ nurturing of trees symbolizes the very essence of ethical living: to think beyond oneself and take actions that may benefit oneself only minimally, but will greatly benefit others, as an oft-retold Talmudic tale relates.

My own tender love for trees came up hard against a fact that, may I be forgiven, I did not know until this newest stage of the bitter war between Israel and the Palestinian people, even though it has been reported in the news over many years. This fact: that the government of Israel has destroyed hundreds of thousands of trees on Palestinian land, and protected Jewish “settlers” as they have destroyed thousands more, dating back at least to 1967, the Six-Day War, and with the destruction (with or without the IDF’s support) if anything only worsening over the past few months. This piece stems from my grief and alienation, which have intensified over the years, took a sharp turn upwards with Israel’s brutal conduct of this war, and are crystallized in the assault on Palestinian trees. To destroy trees in order to attack people is thoroughly despicable. It bears no resemblance to the Judaism I was taught, but of course, the government of Israel has long been out of step with what I love and respect about Judaism.

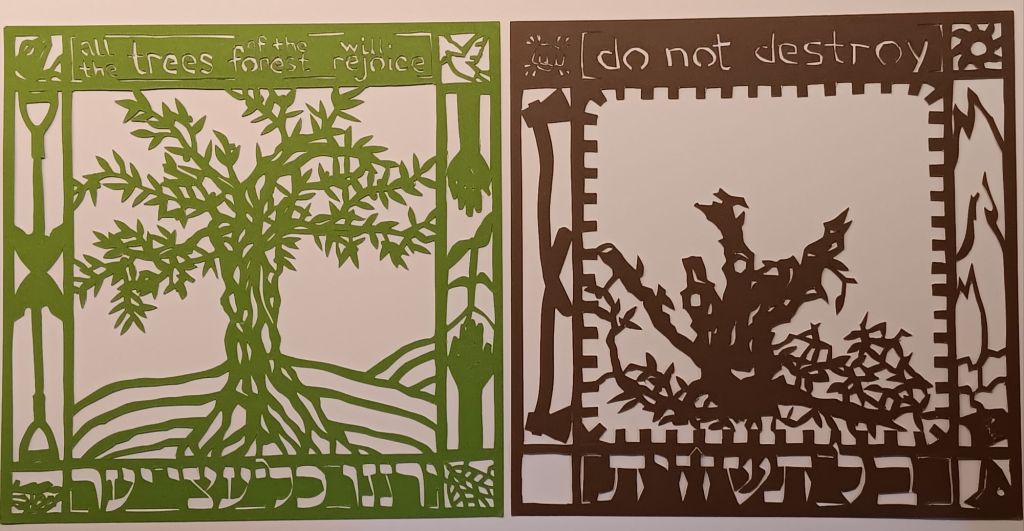

The beautiful vision of the latter appears here on the left panel, with a phrase from Psalm 96 in Hebrew and English, “y’ranenu kal atzei ya-ar,” “all the trees of the forest will rejoice,” framing a thriving olive tree. Around it are (clockwise from upper right) a dove, hands planting a seedling, an insect that lives symbiotically in olive bark, a birds’ nest, shovels, and a lizard that makes its home in olive trees. (I provide this guidance in recognition that my paper-cutting skills are not quite up to my artistic vision, LOL.) On the right side of the diptych, another of the central ethical teachings of Judaism, “ba’al tashchit,” “do not destroy,” frames a dead olive tree. Around the edge are (clockwise from upper right) a bulldozer sprocket, flames and a tear gas canister, a bulldozer blade, emptiness, axes, and a punching fist.

WordPress informs me that this is my 1000th post on Sermons in Stones! Wow. Thanks for coming along for the ride!

In Judaism, there’s a concept called hiddur mitzvah: the beautification of a mitzvah or commandment. It means that while one can discharge one’s duty to fulfill a commandment in a very plain way, adding beauty to it is praiseworthy. There is a commandment to light the Shabbat candles; Jews could mutter the prayer and light two candles that stayed lit for the minimal amount of time and weren’t blown out, and that would fulfill the responsibility. But hiddur mitzvah encourages us to do more: for example, use beautiful candlesticks, preferably ones that are used for no other purpose; use new candles that burn longer than is required; set the prayer to music; gather with our loved ones and hold hands around the candles as we sing together.

Naturally, as I grew up as a Jewish child who loved everything artsy and craftsy, this concept suited me down to the ground. It meant that there was a rich folk art tradition of decorating everything: calligraphed ketubot (marriage certificates), embroidered tallit (prayer shawls), silver filigree spice boxes used at the close of Shabbat, even illustrations from the Book of Esther on graggers, the noisemakers used to drown out Haman’s name whenever the cantor sings it during the Purim services. I made a tallis for my dad, a ketubah for my parents, and more Hebrew school art projects than I can remember. To this day, I remember the exact color and pattern on the contact paper we used to decorate the pushke (charity box) we made in Hebrew school and then kept on a household shelf and filled with our spare change for the rest of my childhood. (Hiddur mitzvah and the many ritual objects are a gift to Hebrew school teachers. So many crafts opportunities!)

Papercuts emerged as part of this tradition. One is supposed to pray facing east if possible,* but there is absolutely no requirement to hang a little sign on the eastern wall inside one’s home. But it became a tradition not only to create such a sign (called a mizrach, which means “east”), but to make it beautiful with calligraphy or, in the 18th-20th centuries in Western Europe, a papercut. This beautification was more than decorative; it had the power to change a person’s awareness of the very meanings of the mitzvah, the same way setting a prayer to music does much more than make the prayer pretty and easy to remember. Imagine someone opening their prayerbook and situate themselves facing east, and as they look up, their eyes fall on an intricate work of art, perhaps portraying the Old City of Jerusalem, or the Western Wall, or the words of a verse from the Torah. Their prayer is now accompanied by visions of places that their people gathered again and again on every holy day. It is witnessed to by the hands of an artist who dedicated her creativity and many hours of her craft to the faith they share. The art invites them into a world of beauty and contemplation during their time of prayer.

This tradition keeps coming to my mind as I work on the papercut I’m making grieving the destruction of millions of olive trees that Israeli “settlers” and the Israeli army have committed over the years in a bitterly self-destructive, anti-halakhic (halakhah is Jewish religious law) attempt to deprive Palestinians of their livelihood. If I were making a mizrach or ketubah, papercutting is the art form I might use. Instead, I’m making a political, largely secular statement–and it occurs to me that art in general is a kind of hiddur mitzvah.

I will eventually write a post here about how my connection to Israel and my conception of what it means to be Jewish in the world after 1948 have changed in response to crimes like the destruction of Palestinians’ trees. Its approach will be logical and discursive, a statement of facts and feelings, and I imagine it will accomplish the basic task of clarifying and expressing my opinion. That would be the equivalent of the unadorned mitzvah. But making this piece, like hiddur mitzvah, does more than that. A work of art, whether a painting, an operetta, a poem, a dance, whatever it may be, isn’t just a statement. It can create an entire microcosm for the viewer to enter and dwell in awhile. It can take us to new depths of understanding that plain words seldom convey. That’s certainly what it is doing for me as the maker.

*All the ones I’ve seen are mizrachim because I grew up in the western Diaspora. Of course, Jews in Asia pray facing west, Jews in Israel pray facing Jerusalem, and Jews in Jerusalem pray facing the ruins of the ancient Temple. The same holds true for Muslims vis-a-vis Mecca, and as far as I know, for all religions that have a tradition of praying toward a particular revered location.

Content warning: image of a grief-stricken child

This is as done as it’s going to get–I think I’m better off starting from scratch if I want to improve it. But the making of it has been painful and beneficial. I am trying, over and over, to embrace my art as a spiritual practice and only secondarily concern myself with the physical artifact that results.

The subject is a child whose name I don’t know, who came to this Gaza hospital a couple of weeks ago when the refugee camp that is her home was bombed. Next to her gaze, and the so-adult expressiveness of her hands, it’s the little details of normal life that wring my heart (as normal as life in a refugee camp can be said to be). Someone helped pull that Minnie Mouse shirt over her head. Someone pulled her hair into a ponytail with that white elastic. Is that person’s blood on her shirt now? Is that person alive? Is she alive?–an ambulance just outside the hospital has been bombed since, and the lack of fuel is turning Al-Shifa into a “mass grave,” although a rumor that a group of Israeli doctors actually called for the hospital to be bombed seems to be sheer invention. (I found reports about it, but searching for the “Israeli news site” they claim to be citing, and the name of the group they claim is doing this, turns up nothing. “The truth is the first casualty of war”; read with care.) 11/7/23, ETA: I saw the same story with full citations here, thanks to Jewish Voice for Peace. At this writing, over 90 doctors have signed the letter. Utterly sickening.

I will never know her story. I just know that I hope neither I nor anyone I love ever has to look upon whatever horror her eyes are seeing.

Since learning about the vast impact of human trafficking–25 million people are estimated to be trafficked each year–I’ve made it one of my major social justice issues. I preached about it, of course; brought a guest to the pulpit to do the same; started an annual tradition of selling fair-trade (i.e., slavery-free) mini chocolate bars for church folks to distribute at Halloween, which was then picked up by volunteers and continues in a great format of connecting our folks directly to the increasing number of sources; helped give new life to a small group, UUs Ending Modern Slavery (UUEMS); with UUEMS, while its brief life flickered again, proposed human trafficking as a study/action issue to the General Assembly of the UUA (only one issue is chosen each year, and it lost); presented workshops and theater productions by survivors of trafficking. But as time went on, and for a variety of reasons–good ones, such as the importance of survivor leadership of anti-trafficking organizations–it became harder for me to find a place in the movement except by donating money. That’s one part of activism for those of us who have money to spare, but I thought there must be other parts also: actions I could take locally, because trafficking happens locally. But the short bursts of internet research I’d do to find one kept leading me down dead ends.

Once again, enter sabbatical. I decided that with that time, I’d persevere and find a way back into the movement to end human trafficking, i.e., slavery. And lo and behold, I found two under my nose. The Bay Area Anti-Trafficking Coalition, whose emails I always get and, um, usually read, was holding a day of education and action on the San Francisco Peninsula. I signed up, attended a few weeks ago, and it was just the kind of labor-intensive, grassroots activism that I had hoped for: helping to ensure that frontline workers in hotels and motels were getting trained to recognize signs of trafficking (as California law requires), and that they had large posters about trafficking prominently displayed where the public could see them (as California law also requires). Such a small moving of the needle, but that’s how things change.

I was also impressed and pleased by their presentation of the issue. While this action focused on disrupting sex trafficking, the presenter emphasized the fact that that is not the only kind of human trafficking. A frustration for me in this movement is that so much of it is focused on sex trafficking, sometimes to the exclusion of all else and sometimes (especially in faith-based initiatives) with an attitude that all sex work per se, all pornography no matter how it’s produced, and frankly, all sex is pretty unseemly. But trafficking happens in all kinds of labor–agriculture, manufacturing, domestic work–and I’m just as concerned about those. And while it’s true that there is a huge amount of trafficking in the sex trade, and that by some studies, the vast majority of people in that trade say they’d like to exit it altogether, I don’t think we treat sex workers with respect, or further our cause, if we act as if all sex work is slavery.

Anyway, a couple dozen of us got the training and went out in pairs–and one of the first people I saw there was a member of UUCPA, and of course we sat together and went out to do the hotel visits together. So much for sabbatical–it looked indistinguishable from a work day! But we kept our conversation on non-church matters like family, and it was great to see her and engage in this issue together.

The second opportunity followed from the first, as they often do. A few of the folks there were from a San Francisco organization (SF Collaborative Against Human Trafficking) that I haven’t gotten involved with before, again for legit reasons, but here I am spending all my time near my home in San Francisco for several months, so I connected with them and immediately learned of an upcoming conference that I hope will lead to ways to address trafficking right in SF. And I have time to go. So I’m going. Incidentally, in the course of following up with them, I learned that a friend of mine, the Hon. Susan Breall, is one of the co-chairs. I could see that as a *facepalm* or confirmation that I’m going in the right direction. I’ll go with the latter interpretation.

Speaking of friends, although UUs Ending Modern Slavery could not get established permanently, in the course of our efforts, I made a dear friend, Deborah Pembrook. We taught workshops together, strategized together, planned anti-trafficking events together, and really enjoyed each other’s company despite the somber reason we were meeting. Deborah died suddenly a year and a half ago, and stepping up my involvement in this issue feels like a memorial to her, and probably the kind she would have cherished the most. Deborah, there are 25 million reasons to bring about an end to human trafficking, and for me, you are one of the most vivid reasons of all.

Earlier in this third week of devastation throughout the state, a member of UUCPA emailed us the news that a fire was burning near Yosemite, just a few miles east of Bass Lake. Bass Lake is the site of Skylake Yosemite camp, where the congregation holds a “getaway weekend” each summer. This year’s was cancelled due to COVID-19. Now the camp itself, not to mention Yosemite and its nearby communities, are approached by a wildfire that has grown very quickly.

The man who sent the email included a photo from Caltopo, to which I guess he must subscribe. I hope they won’t object to my showing it here:

I shared it on Facebook, with a few words about all the loss and sorrow we are holding. Then, a while later, I checked my Facebook page, saw this image in tiny, thumbnail format, and had three thoughts in quick succession: “What is that?” / “It’s beautiful” / “Ohhh. The Creek Fire map.”

I knew right then that I needed to draw it, to spend time with, if not make sense of, the swirl of feelings it evoked. The above are three very small drawings, each 2 x 1.5 or 2 x 1.75 inches, in colored pencil, done earlier today.

Day 49 of #100days of making art

Until a week ago–heck, two days ago–I thought people who called for a dissolution of police departments were crazy fantasists. Sure, we should funnel more money into social work, education and other measures that we know actually prevent crime and improve the lives of our people. But defund the police? We do have laws, I thought, and we do need to enforce them.

I’ve changed my mind. Yes, as long as we’re an archist, as distinct from an anarchist, country, we need to empower people to act when laws are broken, but we need to start from scratch. The police of our country have always been pulled two ways: protect the ill-gotten gains of robber barons against the poor who press to receive their due, or protect the people’s rights? Be the legitimized face of white supremacist terrorism, or protect everybody? Act as judge/jury/executioner, or respectfully turn over suspected violators of the law to the courts?

This week they have chosen the evil path over and over, and it’s just one bad week in 250 bad years. Time for a new way.

“Or,” ink and colored pencil on a page of The Penguin Atlas of the Ancient World, 21 x 17 cm

More about this piece here.

#100days

Eh, I said in my last entry that I’d post a photo of my next piece about ancient and current empires when it was finished, but why wait? Here it is in progress. Source text: The Penguin Atlas of the Ancient World.

#100days

I’ve now been making art every day for over a month. I fell into my current series of projects by accident, as is so often the way, and am now happily spelunking in the caves of altered books, maps, U.S. politics, and white supremacy.

It started when I wanted to find a book to (photocopy and) alter. I poked around on our nonfiction shelves and came upon The Penguin Atlas of Ancient History, which I hadn’t even known we had. One of the benefits of living with a partner is that they spent decades accumulating books too, and even after 15 years together, I’m still discovering some. It is full of maps, and I love maps, so I pulled it out, found a couple of intriguing words on one of the text pages, and got to work.

The first word I noticed was “administration,” and another was “Nineveh,” which reminded me of a phrase about our future fate being like that of “Nineveh and Tyre” in some poem or other. Yeats, maybe.

The poem kept echoing in my head, until I had to look it up (ah, bless the internet) and re-discover it: not Yeats, but Rudyard Kipling, who had such a strange talent for reminding empire of its limitations even while proclaiming its glories.

Reading about these ancient cultures, and seeing all the maps showing the dominance of peoples whose names I’d never even heard of, like the Scythians, is like coming across the colossus of Ozymandias (Rameses II) in the desert–another poem that’s rattling around in my head. Some of these nations lasted for millennia. Ours hasn’t made it to its 250th birthday yet, and I’m wondering what shape it will be in when it gets there. So the words I’m highlighting as I draw my maps are about the collapse of our democracy from hostile forces, foreign and domestic.

I’ve also always been moved by the story of Nineveh in the book of Jonah. If an ancient city, one of the great ones of its time, could summon that kind of repentance and return to its ideals, can’t we?

Another theme that emerges without the author’s having intended it is the narrowness of his assumption that the “ancient world” consists of the Mediterranean, with forays as far as England to the north, western India to the east, and Ethiopia to the south: basically, the trading partners of the empires of the Mediterranean. The book was published in 1967. I showed it to my daughter as an example of the kinds of things I was taught in school, where our books were published around that time. It was a quiet, background kind of white supremacy, a constant hum informing us that nothing worth knowing about happened in sub-Saharan Africa, Oceania, the Americas, or most of Asia until Europeans got there.

I saw with some excitement that there is a New Penguin Atlas of Ancient History: Revised Edition, published in 2002, but alas, it still only covers the same region. A grand opportunity wasted to, if not expand the book, then at least make the title accurate.

I’ll post a picture when I’m done with my new piece.

#100days

Oh, and stop blowing that “anti-Semitic” dog whistle at me, expecting me to wag my tail and join you. I know the difference between being critical of Israel and being anti-Semitic. I’m pretty critical of Israel myself. Two powerful forces in my life taught me that criticism is a crucial part of free, loving engagement: the First Amendment and the Jewish faith.

I don’t take kindly to being manipulated by actual anti-Semites, the kind who put Sebastian Gorka and Steve Bannon in the White House, or tolerate their presence; who gear their every utterance to what will please The Daily Stormer‘s readership, or smile at the poll numbers that result.

I know who will have my back if you drop the last pretence and come for me, and it won’t be the so-called Christians who sing your praises. It will be the people that you and they are trying, in your cynicism and naivete, to divide me from now.

You and your white nationalist, white supremacist fans sometimes make me feel ashamed to be U.S. American, but the people you keep describing as my enemies?: they restore my pride in my country.

We are united by a force you don’t understand. Because of it, we are stronger than you, and we will never be defeated.

Recent comments