You are currently browsing the category archive for the ‘art’ category.

All in my 5×7 sketchbook in graphite.

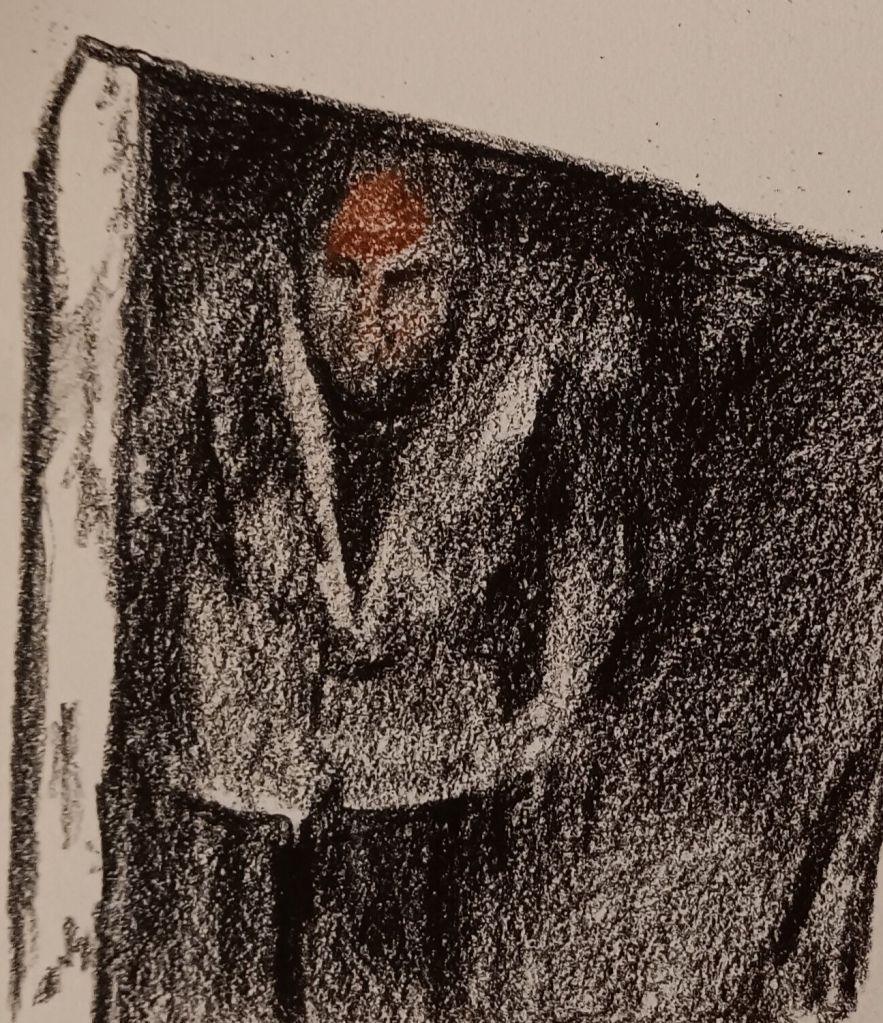

I have been listening to people’s stories from Israel and Palestine (This American Life has had several lately) and looking at photos of the devastation. In one photo, the figure of a man standing in a doorway of a shattered building (his home?) seems so small, but also immovable in both dignity and grief. I was hearing the same in the stories, all the stories. I kept coming back to that photo until I realized that he was the person I needed to draw.

The drawing is conté crayon, about 4″ x 3″. The photo is below. I have seen it with various captions on different websites, usually with some editorial slant, but all agree that the photo is of Khan Yunis, in the southern Gaza Strip, and shows the result of an airstrike by the Israel Defense Force on December 6, 2023.

What I’ve been drawing for the past two weeks. One small sketchbook page of pencil and marker doesn’t seem like much, but I’ve been doing it every day–sometimes for a long stretch, sometimes for only five or 10 minutes–and making art a steady part of my life even as job, family, and household fill my time, is an effort and an anchor.

Also, there’s a story with this one. The image came into my mind of dark, receding layers of concentric and overlapping circles, and some brighter rings in the foreground. As is often the case, I had no idea why, or what it might come to mean, but I was intrigued. “Huh,” I thought. “I’ll have to draw that one of these days,” and I went on with whatever I was doing.

Well, I had just given a sermon on the difference between our popular conception of some people’s being geniuses and the much more liberating, fruit-bearing idea of occasionally having a genius, like a spirit that visits. Elizabeth Gilbert writes about this in her book Big Magic, and as soon as I read it I was captivated, or rather, freed, by it. In the sermon, I talked about ways we might invite a genius to visit us, and keep it around when it does, and the most important one was to heed what it says.

So I heard myself not-heeding. Telling the genius this wasn’t a very convenient time. And it wasn’t because I was performing open-heart surgery or driving to an urgent appointment. I just didn’t feel like sitting down and making art. All the little habits of fear and hesitation had me shooing the genius out the door. But thanks to Elizabeth Gilbert, and giving the sermon, and having so many people respond to it, this time I noticed myself saying no and how diametrically that contradicted the advice I had just given. I pushed aside my shabby excuses, got a compass out of the “Sharp things!” drawer in the art room, and tried to put on paper what the genius had shown me in my mind.

Until I said “Maybe later” to the genius, and heard myself saying it, and heard the contradiction, I didn’t realize how habitually I say “Not now.” How I am, in fact, in the habit of saying “no” rather than “yes” to the genii who, by my great good fortune, knock on my door pretty often. I am really excited to discover what might happen when I start to welcome them in.

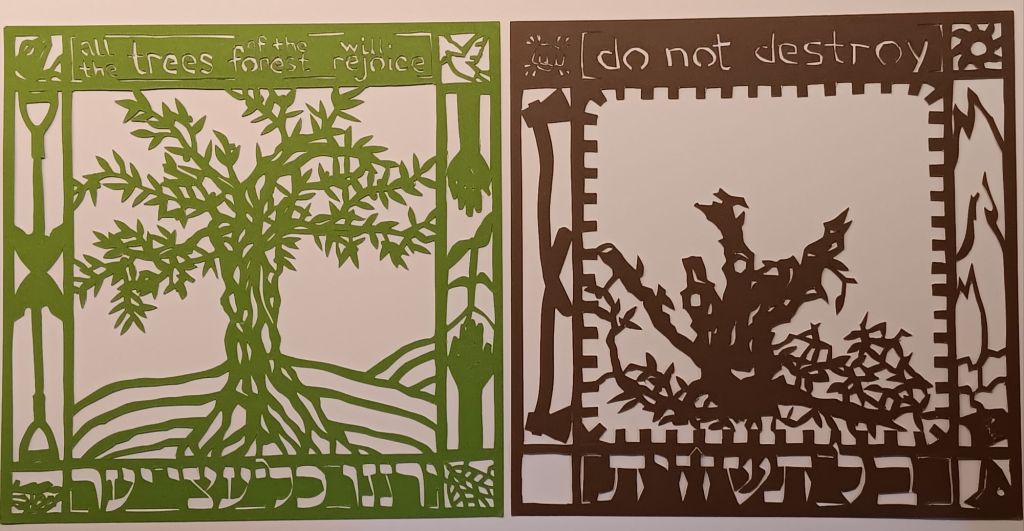

The Judaism I was taught regards trees as a particularly beautiful and sacred part of creation. It is a mitzvah to plant them. Given their slow growth and long lifespans, they are a gift to the future. Humans’ nurturing of trees symbolizes the very essence of ethical living: to think beyond oneself and take actions that may benefit oneself only minimally, but will greatly benefit others, as an oft-retold Talmudic tale relates.

My own tender love for trees came up hard against a fact that, may I be forgiven, I did not know until this newest stage of the bitter war between Israel and the Palestinian people, even though it has been reported in the news over many years. This fact: that the government of Israel has destroyed hundreds of thousands of trees on Palestinian land, and protected Jewish “settlers” as they have destroyed thousands more, dating back at least to 1967, the Six-Day War, and with the destruction (with or without the IDF’s support) if anything only worsening over the past few months. This piece stems from my grief and alienation, which have intensified over the years, took a sharp turn upwards with Israel’s brutal conduct of this war, and are crystallized in the assault on Palestinian trees. To destroy trees in order to attack people is thoroughly despicable. It bears no resemblance to the Judaism I was taught, but of course, the government of Israel has long been out of step with what I love and respect about Judaism.

The beautiful vision of the latter appears here on the left panel, with a phrase from Psalm 96 in Hebrew and English, “y’ranenu kal atzei ya-ar,” “all the trees of the forest will rejoice,” framing a thriving olive tree. Around it are (clockwise from upper right) a dove, hands planting a seedling, an insect that lives symbiotically in olive bark, a birds’ nest, shovels, and a lizard that makes its home in olive trees. (I provide this guidance in recognition that my paper-cutting skills are not quite up to my artistic vision, LOL.) On the right side of the diptych, another of the central ethical teachings of Judaism, “ba’al tashchit,” “do not destroy,” frames a dead olive tree. Around the edge are (clockwise from upper right) a bulldozer sprocket, flames and a tear gas canister, a bulldozer blade, emptiness, axes, and a punching fist.

The nice thing about having my sketchbook with me everywhere is that when we’re waiting for the food to arrive at a restaurant, I can draw what’s on the table. When we were in Solvang, we went to dinner at a place that had these nice oil lamps on the tables, with their irresistible patterns of shadow and light.

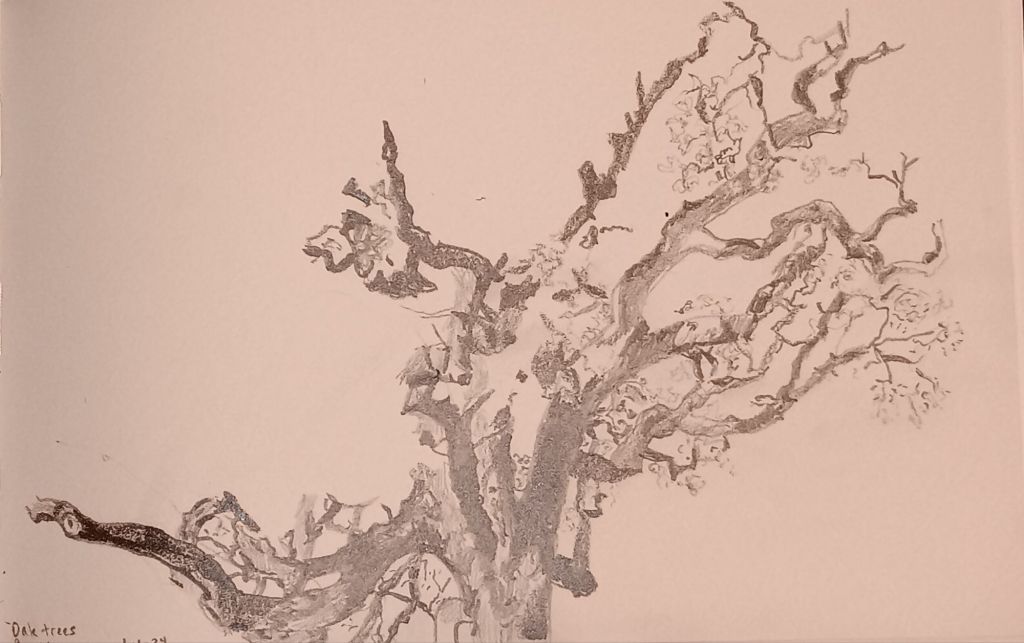

California’s oak trees always say “draw me,” and I am usually too intimidated to heed them. I like this drawing, though. It’s an exercise in not being too specific–just following the general patterns of the tree. That’s really difficult for me for a variety of reasons. I don’t know if I’ll finish it, but I’ve returned to it for the past few days, having gotten a start on it at the winery where it grows while we were still in SoCal.

We went south for a few days after Christmas to meet up with friends and hike in the beautiful Santa Ynez Mountains. The route took us down through the Salinas Valley. At one point a patch of sun on the otherwise clouded hills was so striking that I considered stopping to take a picture, or asking Joy to take one out the window as I drove, because I knew I’d want to draw it later. The moment passed, unrecorded except in my mind, and when we got to our destination, I went looking on the internet for a reference photo. I really wanted it to be of these same hills. Nothing quite captured the quiet drama of that illumination–moral: take the photo when it strikes you–but this one was pretty. Thank you, Shutterstock (photo 1055815059).

WordPress informs me that this is my 1000th post on Sermons in Stones! Wow. Thanks for coming along for the ride!

In Judaism, there’s a concept called hiddur mitzvah: the beautification of a mitzvah or commandment. It means that while one can discharge one’s duty to fulfill a commandment in a very plain way, adding beauty to it is praiseworthy. There is a commandment to light the Shabbat candles; Jews could mutter the prayer and light two candles that stayed lit for the minimal amount of time and weren’t blown out, and that would fulfill the responsibility. But hiddur mitzvah encourages us to do more: for example, use beautiful candlesticks, preferably ones that are used for no other purpose; use new candles that burn longer than is required; set the prayer to music; gather with our loved ones and hold hands around the candles as we sing together.

Naturally, as I grew up as a Jewish child who loved everything artsy and craftsy, this concept suited me down to the ground. It meant that there was a rich folk art tradition of decorating everything: calligraphed ketubot (marriage certificates), embroidered tallit (prayer shawls), silver filigree spice boxes used at the close of Shabbat, even illustrations from the Book of Esther on graggers, the noisemakers used to drown out Haman’s name whenever the cantor sings it during the Purim services. I made a tallis for my dad, a ketubah for my parents, and more Hebrew school art projects than I can remember. To this day, I remember the exact color and pattern on the contact paper we used to decorate the pushke (charity box) we made in Hebrew school and then kept on a household shelf and filled with our spare change for the rest of my childhood. (Hiddur mitzvah and the many ritual objects are a gift to Hebrew school teachers. So many crafts opportunities!)

Papercuts emerged as part of this tradition. One is supposed to pray facing east if possible,* but there is absolutely no requirement to hang a little sign on the eastern wall inside one’s home. But it became a tradition not only to create such a sign (called a mizrach, which means “east”), but to make it beautiful with calligraphy or, in the 18th-20th centuries in Western Europe, a papercut. This beautification was more than decorative; it had the power to change a person’s awareness of the very meanings of the mitzvah, the same way setting a prayer to music does much more than make the prayer pretty and easy to remember. Imagine someone opening their prayerbook and situate themselves facing east, and as they look up, their eyes fall on an intricate work of art, perhaps portraying the Old City of Jerusalem, or the Western Wall, or the words of a verse from the Torah. Their prayer is now accompanied by visions of places that their people gathered again and again on every holy day. It is witnessed to by the hands of an artist who dedicated her creativity and many hours of her craft to the faith they share. The art invites them into a world of beauty and contemplation during their time of prayer.

This tradition keeps coming to my mind as I work on the papercut I’m making grieving the destruction of millions of olive trees that Israeli “settlers” and the Israeli army have committed over the years in a bitterly self-destructive, anti-halakhic (halakhah is Jewish religious law) attempt to deprive Palestinians of their livelihood. If I were making a mizrach or ketubah, papercutting is the art form I might use. Instead, I’m making a political, largely secular statement–and it occurs to me that art in general is a kind of hiddur mitzvah.

I will eventually write a post here about how my connection to Israel and my conception of what it means to be Jewish in the world after 1948 have changed in response to crimes like the destruction of Palestinians’ trees. Its approach will be logical and discursive, a statement of facts and feelings, and I imagine it will accomplish the basic task of clarifying and expressing my opinion. That would be the equivalent of the unadorned mitzvah. But making this piece, like hiddur mitzvah, does more than that. A work of art, whether a painting, an operetta, a poem, a dance, whatever it may be, isn’t just a statement. It can create an entire microcosm for the viewer to enter and dwell in awhile. It can take us to new depths of understanding that plain words seldom convey. That’s certainly what it is doing for me as the maker.

*All the ones I’ve seen are mizrachim because I grew up in the western Diaspora. Of course, Jews in Asia pray facing west, Jews in Israel pray facing Jerusalem, and Jews in Jerusalem pray facing the ruins of the ancient Temple. The same holds true for Muslims vis-a-vis Mecca, and as far as I know, for all religions that have a tradition of praying toward a particular revered location.

I am working on a diptych of olive trees in Israel and Palestine. A few minutes after the image came to me, the medium followed: traditional Jewish papercuts, an art form I have loved and admired for a long time, but have never tried. I’m loving it.

According to Wikipedia, papercutting was done throughout the Jewish world, and was especially popular in the 18th and 19th centuries in Europe. But between the fragility of the medium and the destruction of so many Jewish possessions in the Holocaust, only a couple hundred of the pieces from that period still exist. In recent decades, artists have rediscovered and reclaimed papercut art, and one sees it often in sacred art: decorating ketubbot (religious marriage certificates) and mizrachim (signs designating the east, toward which Jews face in prayer), illustrating passages from the Tanakh or Talmud.

This piece is going to express sorrow and bitterness about an inner conflict, within me and within Judaism: the conflict between some of the most beautiful, wise teachings of Judaism and the policies of the modern state of Israel. The beauty of the art form is one ingredient of that bitterness. This half of the diptych, the happy half, is not quite half finished.

I hope you’ll check out my column, Ask Isabel: Advice for the Spiritually Perplexed or Vexed, now in its tenth week!

Subscribe for free to receive it via email each Tuesday.

That’s the tentative title for what might end up being a painting. I envision this writing scratched in paint or ink so that an under-layer of paint or ink shows through, but some kind of dry medium might also work, or maybe colored pencil over an ink wash–the layers are important. I have tried it in pencil before, when I first got the idea seven years ago. I know it was that long ago because we were living in Oaxaca then. I didn’t have the idea of making a portrait out of scribbled-out, obscured words at that time. I know I have that sketch somewhere and I’m curious what my earlier idea was.

The legible text tells a story. The most important points are here, but it will be longer and go into more detail in the next version. There’s more I want to write, but as this is quite small, the size of my sketchbook, I ran out of paper before I ran out of things to say.

This whole project makes me think a lot about my friend Karen Schiff, who is also an artist (check out her great drawings and writing about art here).

I didn’t realize until after I’d drawn this that the location has a name very similar to a name in our family, the branch that came to the US from Lebanon.

Recent comments