You are currently browsing the category archive for the ‘uncategorized’ category.

Thanks to friends of our family who owned a house near the Headlands in Rockport, Massachusetts, I got to visit this lovely town once when I was a child. All I remember from that visit is a house with circular rooms, the quality of the light in the house, and a feeling of complete delight.

When we got the chance to visit Rockport this month, I knew I had to find that house. It turned out to be easy to find online: my mother confirmed my memory of its being round, so I put “round house Rockport” into a search engine and was immediately taken to a vintage photo of the studio of Harrison Cady, who was a well-known illustrator in his day. I hadn’t remembered that it was once his house, or that he had lived in Rockport, but I knew he was related to our friends, so there you have it: that’s how they came to have a house here. Joy and I walked up to it on my first day here.

It’s right on the water:

The view from the place we’re staying is no slouch either:

From the Harrison Cady house, we went on to the Headlands, which looks out across the harbor and out to the Atlantic, which is located where an ocean ought to be. I’m sort of joking, since after 20 years living a few miles from the Pacific, I’ve stopped thinking of it as being on the wrong side, but it still feels more natural to have the water “on my right” as I face north.

Another difference between here and California is how much longer Europeans have been here in New England. You don’t see buildings from the 17th and 18th centuries in California.

This house was constructed more recently. In the period when our daughter had tiny imaginary friends everywhere, she would have loved it.

Also on my first day, we walked around the corner to the Unitarian Universalist Society. I didn’t expect it to be open on a weekday morning, but when I tried the front doors anyway, a man waiting in a car called out that he was a member, and could he help us? That question is used so often to mean “What do you think you’re doing?” that it’s hard to convey that he really meant it, but he really meant it. He and his wife had stopped by to take care of a couple of things, so they immediately gave us a tour. In the lovely, sun-drenched sanctuary, we discovered that, like UUCPA, they have a chalice shaped like a tree. Isn’t it striking? I like the nest for the flame.

They have beautiful rooms upstairs too, especially the tiny room for the tiniest children, with its windows on three sides giving views onto the ocean and town. We also got to see their solar panels, installed just last summer. Sadly, I am fitting this vacation in between Sundays, so I can’t attend a service. But it was great to meet a few UUs, who were as warm and friendly as could be.

This is as close to totality as we got in San Francisco. But at least the sky was unclouded. The “big sun” must be some kind of glare effect.

Listening to scientists describe totality, I want to see one before I die. Maybe I’ll go to Alaska in 2033, take in Denali and the Northern Lights while I’m at it. In the meantime, I’m watching it on NASA’s livestream right now.

I have a gym membership, but a few times recently, I’ve put together a home, calisthenics (bodyweight only, no weights) workout in order to keep up with my schedule while traveling. I liked it pretty well, so I thought maybe I would switch to these workouts entirely. It would certainly save me a lot of money. My main concern was whether they would be rigorous enough, being that we have no equipment except a couple of five-pound weights. Bodyweight is all very well, but eventually it may get too easy, and then I won’t have weights on hand to add difficulty.

I can now rest easy on that point. I did some research, created a four- or five-exercise regimen for a pull day, and started in on it. I completed one of the exercises this afternoon, a superman, and have been knocked absolutely flat ever since. Whoof. Lying in bed, aching all over, and now going to take a couple of ibuprofen and a nice soak. It’s possible that I’ll eventually get so fit that I’ll need to get some equipment, but that time is clearly a long way off.

I’ve just published my 20th Ask Isabel column. I’m still having fun.

Ask Isabel: God and infinity and eternity, oh my!

If you like, please share. If you want to get a ping each week when it posts, please subscribe.

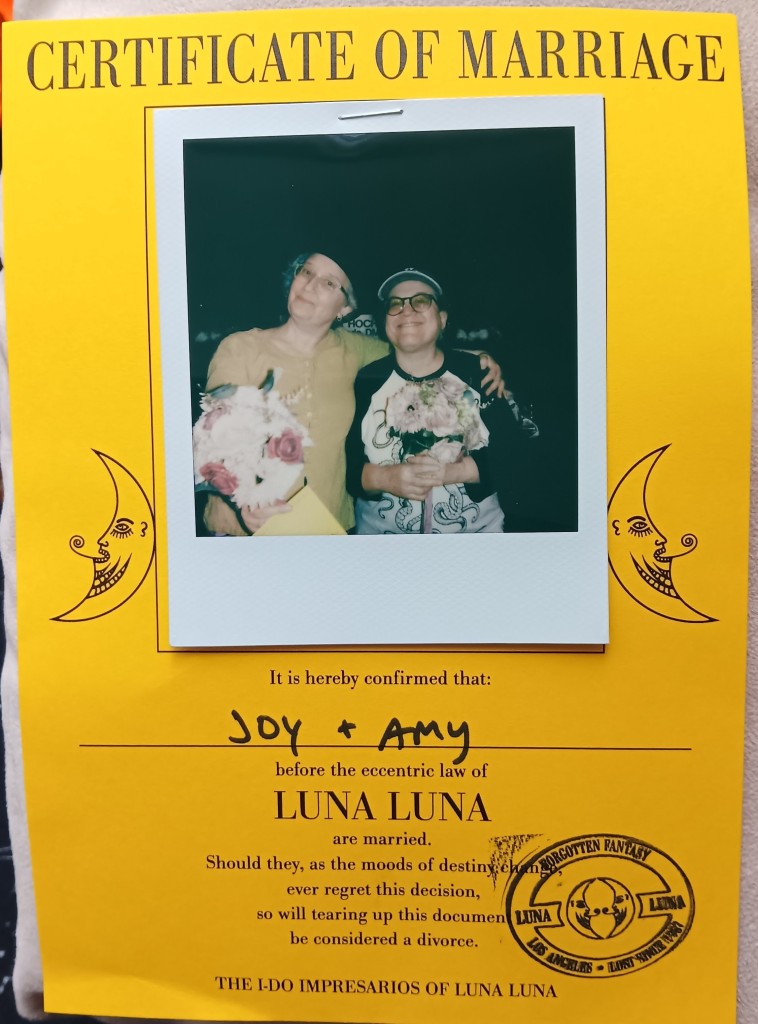

Joy and I went to my mom’s in SoCal for the long weekend, and before plans had even taken shape, all three of us said, “Let’s go to Luna Luna!”

Luna Luna was a combination art extravaganza and amusement park, conceived by André Heller and created by an incredible roster of artists: Sonia Delaunay, Keith Haring, David Hockney, Salvador Dali, Jean-Michel Basquiat, Kenny Scharf, Rebecca Horn, Roy Liechtenstein, Georg Baselitz, and many others. Heller asked them if they wanted to create an art amusement park, and they said YES. It opened in Hamburg in 1987, ran for six weeks, and then . . . disappeared. The plans to go on to more cities fell through, and there was nothing to do but pack it all up into 44 shipping containers.

There was a documentary at the time, and these artists weren’t exactly obscure, yet it was all but forgotten. Several years ago, after pulling together a team that crucially included Drake as a funder, Heller and his son brought the pieces out of storage. A small number of them are resurrected in Los Angeles, and even though you can’t go on the rides, it really feels like an amusement park, not a gallery. After this run ends in May, Luna Luna will go to New York. Maybe one day kids will be able to ride the Keith Haring carousel and a classical violinist will once again perform with a professional flatulist in Manfred Deix’s Palace of the Winds (fart jokes were apparently even more amusing to 18th-century Austrian adults, including Mozart, than they are to 21st-century US American fourth graders).

No one need wait for another of Luna Luna’s features, however: André Heller’s Wedding Chapel. “Do you want to get married?” I joked to Joy. “Yes!” she said, sincerely, and soon we were standing before a very sweet celebrant, who took the time to ask how long we’d been together and other details of our lives, sighing sympathetically when we said our first wedding wasn’t recognized by the law. Then we picked up bouquets and I put on a top hat. Joy already had her Flying Spaghetti Monster baseball cap, and I thought that it introduced a key spiritual element, so I urged her to stick with it rather than take one of the top hats or veils the chapel offered. We re-exchanged rings and kissed. My mom video’d the whole thing, and the people gathered around cheered, while one impresario rang a bell and another took our photo. It was fun and funny and lighthearted and art-infused, just like our life together. And to look into my wife’s eyes as she was asked if she would “venture an adventure through galaxies of love” with me, and to have her gaze back as she said that she would–that was a sacred moment I will always remember.

We were married in the eyes of our family and church in 2005, and again in 2008 when the state of California opened its eyes. So now we have our third marriage certificate. It’s good to revisit our decision now and then and remind ourselves that we would marry each other all over again.

I didn’t realize until after I’d drawn this that the location has a name very similar to a name in our family, the branch that came to the US from Lebanon.

I was 40 before I heard the term “executive function,” when a parent at church said her child was getting some coaching in that area: the cluster of cognitive functions, such as working memory and emotional regulation, that make planning, problem-solving, and time management possible. Like many, probably most, people who got that far in life while regularly misplacing objects, forgetting any appointment that wasn’t written down and some that were, underestimating the time tasks would take, and overestimating the time I had in my day, I had a lot of shame and internalized criticism about these difficulties. In a shabby little corner of my mind, I even thought it was indulgent to consult a coach instead of just sucking it up and doing what most other people seemed to manage on their own.

Another ten years along, I had managed to shed a lot of that “just do it” nonsense. Around the same time, I considered that I might have ADHD; discovered that I didn’t tick the necessary diagnostic boxes; but also learned that a lot of the advice that ADHD-wise experts give was useful to me also. It seemed to fit the way I thought and the difficulties I had. (I distinguish between these experts and the people who just give supremely unhelpful advice like “Have you tried writing things down?,” the psychological equivalent of tech help that asks you if your computer is plugged in.) It occurred to me that if there were people who helped children and teens develop their executive functions, there might be coaches for adults, too. There are, and they do often work with people with ADHD–but they don’t care if you have the diagnosis. Presumably they have also noticed that the approaches that help folks with ADHD help a lot of us who live on some point of the spectrum between Diagnosably Neurodivergent and Textbook Neurotypical, if the latter exists.

The approach of sabbatical is a time to reflect: What would I like to do differently in my ministry, or do more, or do less? What do I want to learn during this time that could help me accomplish that change? One theme that emerged from my reflections was: I’d like it not to be quite so hard. Or rather, I’d like the hard parts of ministry to be the hard parts: staying present with people in times of grief and uncertainty. Crafting worship that is engaging and deep. Strategizing how to help a community adapt to cultural changes like a global pandemic, and respond courageously to threats to democracy. I wanted to be able to put more energy into those aspects of ministry, and not have it sapped by searching for files that were sitting right there yesterday, damn it or scrambling to meet a deadline I had forgotten about until it was upon me. I decided that sabbatical would be a good time to see whether some executive function coaching could make what was easy for some people easier for me. It sure didn’t feel like something I could squeeze in to my work week.

The only down side of getting my coaching during sabbatical was that maybe, lacking the daily influx of emails, meetings, etc., I would not have enough material to work with. No fear. Within a month I had plenty of leisure-time examples of executive dysfunction to analyze with a coach. I began meeting with Kelly in August. And it’s a profound relief to talk about these things with someone who understands “I wrote it on my to-do list, but then I was scared to look at my to-do list,” and who can help me come up with ways to overcome that fear: ways that actually work, not for other people but for me. Just like in sports, the coach can’t do the work for you, but a good one can help focus your attention on what will make the biggest difference between today’s training session and the next one.

I don’t have any illusions that I will be an organizational genius by January. These functions may always require particular attention to run smoothly. But I have some hope that they can run smoothly, most of the time, if I keep working on them–and that’s something I haven’t felt in many, many years.

I hope you’ll check out my new column, Ask Isabel: Advice for the Spiritually Perplexed or Vexed

To receive it via email each Tuesday, subscribe for free!

Content warning: image of a grief-stricken child

This is as done as it’s going to get–I think I’m better off starting from scratch if I want to improve it. But the making of it has been painful and beneficial. I am trying, over and over, to embrace my art as a spiritual practice and only secondarily concern myself with the physical artifact that results.

The subject is a child whose name I don’t know, who came to this Gaza hospital a couple of weeks ago when the refugee camp that is her home was bombed. Next to her gaze, and the so-adult expressiveness of her hands, it’s the little details of normal life that wring my heart (as normal as life in a refugee camp can be said to be). Someone helped pull that Minnie Mouse shirt over her head. Someone pulled her hair into a ponytail with that white elastic. Is that person’s blood on her shirt now? Is that person alive? Is she alive?–an ambulance just outside the hospital has been bombed since, and the lack of fuel is turning Al-Shifa into a “mass grave,” although a rumor that a group of Israeli doctors actually called for the hospital to be bombed seems to be sheer invention. (I found reports about it, but searching for the “Israeli news site” they claim to be citing, and the name of the group they claim is doing this, turns up nothing. “The truth is the first casualty of war”; read with care.) 11/7/23, ETA: I saw the same story with full citations here, thanks to Jewish Voice for Peace. At this writing, over 90 doctors have signed the letter. Utterly sickening.

I will never know her story. I just know that I hope neither I nor anyone I love ever has to look upon whatever horror her eyes are seeing.

Yesterday the fifth Ask Isabel column hit the email inboxes. It’s getting more attention: more subscribers, more readers, and the first Like and comment!

This week’s column asks whether God matters.

You can see all of the columns here, and of course, subscribe (it’s free and spam-free) and also submit a question if you are so moved.

I’m really enjoying delving into the many questions people have. Clearly, even for people who aren’t religious and don’t think much about spiritual matters, these issues make themselves felt: via the wider community, in conversations (and sometimes conflicts) with family and co-workers and friends and neighbors, in chance encounters, through memories of communities that were once important to them. It’s an education just to hear what people are thinking about.

Which will it be?

Something big has taken up residence in our garage.

Recent comments