You are currently browsing the category archive for the ‘grief’ category.

Occasionally, it’s crossed my mind to wonder whether my parents would want me to say Kaddish for them after they died. I don’t think I could promise getting to a morning minyan every day for the full 11 months, but if it were important to them, I’d make it a regular practice. I know that for my own sake, I will light yahrzeit candles every year. Seeing one on the kitchen counter now and then kept the rhythm of the year, reminding me that my mother had her own heart-calendar. (I remembered exactly which dates of the secular calendar my aunt and grandmother died, but one marks the yahrzeit on the Hebrew calendar, and I didn’t know those dates. But Mom did.) Without ever consciously deciding, I’ve always known that I would have that candle for my family in time, a reminder and beacon for over 24 hours until it was entirely consumed. L’dor va’dor, from generation to generation, is a common phrase in Judaism, and lighting a candle continues a ritual that speaks to me and that each generation has observed before me. Kaddish is different, though, at least as it is usually observed: not in the privacy of one’s own home, but communally. It’s one of the prayers that requires a minyan, the quorum of ten adults.

Never having asked him while he was alive, I thought about it after Dad died last month, and was pretty sure that if we had talked about it, he would have made a dismissive gesture and said that he didn’t believe in that stuff anymore. Then he probably would have told a story about helping make up a minyan for the sake of a friend in the synagogue when they were saying Kaddish, or said something else to move the moment on. Or said that if it were meaningful to me, then sure, I should say it. I am still Jewish in some indelible ways, but since the Kaddish is famously focused on praising God (it doesn’t mention death), and since lauding a God I don’t believe in doesn’t bring me comfort, I haven’t said it for my own sake.

Today, though, I went to shul for the first time since my nephew’s Bar Mitzvah, as part of Neighboring Faith Communities, a program I’m co-leading in our congregation. We learn about. I’m teaching the adults and a few lay leaders are teaching a group of middle schoolers, and they make the visits together. I haven’t joined them so far because the visits have all been on Sunday mornings, but as soon as we set the date to visit Congregation Beth Am, on a Saturday morning of course, I put it on my calendar. I had never been, and it was enjoyable.

What I didn’t consider until a few minutes into the service, though, was that there would be a Mourner’s Kaddish at the end of the service and that I was a mourner. I quickly looked over the prayer to make sure I could still say it, as I know my Hebrew reading is a little rusty; the Reform prayer book has transliterations of everything, but I find them harder to read than the Hebrew script. (To be precise, the Mourner’s Kaddish is in Aramaic, but the script and pronunciation of the two languages are the same.) And I felt a strange frisson, to enter the world of Jewish mourners, visibly and audibly, and with members of my congregation around me to boot. When we got to that point in the service and it turned out that Beth Am’s practice is for everyone to say it together, the frisson was replaced by an equally unexpected letdown. But the rabbi asked us to call out the names of anyone we were remembering, I said “David Zucker,” as others spoke the names beloved to them, and then, as we began the prayer, I was back on the long, upholstered pews of Temple Beth Sholom, my father rising next to me to say Kaddish for his father. L’dor va’dor, no question. The tears rose, my voice dried up, and I had to whisper the beginning of the second paragraph: “Yitbarach v’yishtabach, v’yitpa’ar v’yitromam v’yitnaseh” . . . I managed to get my voice back by “b’rich hu,” but I was wrung out.

We’ll say the Kaddish as part of Dad’s memorial service in April. It’s an important part of my sister’s practice, and it seemed right to suggest it when she and I met with the (Unitarian Universalist) officiant, but I wasn’t thinking about what it would mean for me personally. Now I am.

I am in the midst of a week’s study leave. As usual, I didn’t really clear my desk before this “break from usual responsibilities,” much less write the reflection and eulogy I will need for Sunday, so it is far from a week of pure study. But I am managing to spend most of my time immersed in two topics.

One is death and grief. My first book of the week was Irvin Yalom’s Staring Into the Sun: Overcoming the Terror of Death. By pure chance, the reading for my women’s group was an excerpt on different ways of incorporating past losses into our lives, from On Living, a memoir by hospice chaplain Kerry Egan. Tuesday, I was browsing the natural history section of a bookstore and stumbled upon H is for Hawk, which thanks to a review, I knew was not only natural history but very much about the author’s process of mourning her father’s death. It is now on the pile. The next day, I was browsing the DVD section on a rare trip to San Francisco’s Main Library, and remembered that I’ve been looking for the first season of Six Feet Under for a while. They have it! I’ve watched two episodes, and the people who told me it’s a really good look at death and grief are right.

The other area of immersion is African American history and fiction, a long-term remediation project to fill the gaps in my education and better equip myself to fight white supremacy. I’ve read Bud Not Buddy, a children’s chapter book by Christopher Paul Curtis. I’m also reading March by Geraldine Brooks, with the grain of salt I keep on hand for books about the black experience by white people, especially fiction, but so far, so good: it’s teaching me some things about the Civil War years that I didn’t know, and I’ve been nibbling at this book since December so I really want to finish it. Next up is Ida: A Sword Among Lions, an intimidatingly thick biography of Ida Wells by Paula Giddings–many thanks to Mariame Kaba for the recommendation.

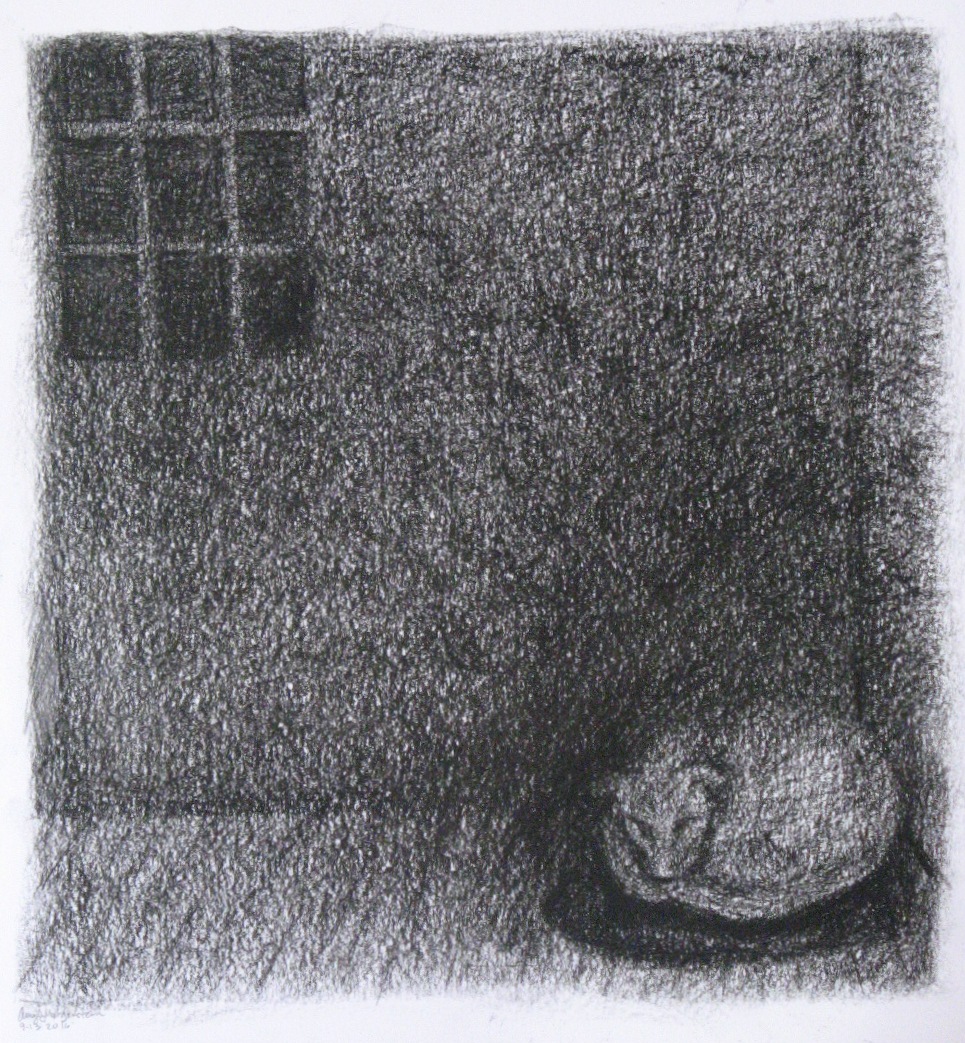

Grief (with thanks to Denise Levertov), conte crayon on paper, 11 x 12 inches

Levertov’s poem “Talking to Grief” gave me this image that helps me to acknowledge and honor such sorrows; I’m so grateful. And grateful also to my spiritual director, the Rev. Sandee Yarlott, for the language of “acknowledging” and “honoring.”

While I was working on the drawing, I returned to the poem and decided to try to translate it into Spanish. Robert Frost said that poetry is what gets lost in translation, and it’s probably more than I can do to get a literal translation right, much less evoke the poetry of the original. I have a lot of questions for my Spanish teachers when we meet next week, such as “what’s the nearest Spanish equivalent to ‘grief’?” and which of the various terms for “mat” evokes the kind you’d be likely to give to a stray dog, and whether the tone is at all like Levertov’s. But here’s my first pass at it. Friends who are fluent in Spanish, I’d love your input on the translation, if you’re so inclined. The English original is here.

Hablando a Luto

por Denise Levertov

Ah, Luto, yo no debería tratarte

como un perro sin hogar

que venga a la puerta trasera

por una corteza, por un hueso sin carne.

Yo debería confiar en ti.

Yo debería engatusarte

para entrar la casa y darte

tu propio rincón,

Una estera gastada para acostarte,

tu propio plato de agua.

Tú piensas que yo no sé que hayas estado viviendo

debajo de mi porche.

Tú añoras que tu verdadero lugar esté preparado

antes de que el invierno venga. Necesitas

tu nombre,

tu collar y chapa. Necesitas

el derecho de ahuyentar intrusos,

considerar

mi casa la tuya

y yo tu persona

y tú mismo

mi proprio perro.

This summer’s soundtrack seems to be Bob Dylan’s “Everything is Broken”: “Seems like every time you stop and turn around, something else has just hit the ground.” I’d like to take a page from my soon-to-be-colleague Lauren Way and ask, “What’s good in your life? What’s bringing you joy? What are your victories, small or large?” As she says, we could sure use some good news right now. The comments form is at your disposal.

It’s the first day of Lent and I’ve decided that my practice this year will be to write daily on this blog. I have let it slip, and I miss the discipline of thought that it requires.

I made mental notes about Gravity back last fall when I found the one showing in San Francisco that fit between my drawing class and my time to take my daughter to music, at a small theater that only showed it in 2D. It being Monday afternoon, it was practically a private showing. If you haven’t seen the movie, you may want to skip this post, because here be spoilers.

I loved this movie. I know it drives people crazy who know and care what astronauts do. I’m sure I would froth at the mouth about all the mistakes in a movie about ministers, but since I am not particularly interested in astronauts or the proper procedures for maintenance of space telescopes or the International Space Station, I just enjoyed what the movie was really about, to this viewer. It isn’t supposed to be a documentary about space. To me, it’s about grief, and how difficult it is to return to daily life when all you want to do is float away and never feel anything again.

And before I even knew that, at the very first shot, I started to cry. There they were, little tiny people floating in this unimaginably large, indifferent expanse. As the introduction says, life in space is impossible. And then the moviemakers show us people in space. I thought, “That’s us! We’re all floating here in space for a tiny amount of time and then phut,” and I just stayed in that existential crisis for the following two hours. I thought that that was a different emotional issue than grief–me fussing about my own mortality instead of my never-absent dread that my daughter might precede me into death–but several months’ rumination on Gravity have made me realize that maybe they are really the same sorrow.

In the end, ironically enough, it is a very small movie, in the sense that it isn’t epic in scope but about a single person coping with a single event that is not newsworthy or noteworthy to anyone much except her. (I like small movies.) A woman’s young daughter has died. The woman, Ryan Stone, doesn’t know how to go on, or how to want to; she hasn’t touched the ground since. On earth, she achieves this by driving as much as possible, always moving. In space, maybe it’s easier to float, but maybe not; when we first see her, she is fighting nausea, and clearly her distress is not just physical. By the close of the movie, however, she wants to live. She digs her hands into the earth, grateful just to be here, and when she stands up on those shaky legs, the camera looks up at her as if at a colossus. With that shot, Cuarón is saying that Stone is heroic, and she is.

One critic couldn’t resist the pun, and wrote (safely after the winner was announced) about the Academy’s choice between “Gravity and gravitas,” the latter being represented by 12 Years a Slave. I can’t compare this movie to 12 Years a Slave or any of the other Best Picture nominees, because it’s the only one I’ve seen so far, but I cannot agree that Gravity lacks gravitas. The writers named it well. “Gravity” stands for one of the weightiest, most serious losses a person can endure. It is what tethers us to reality and all the pain it brings, rather than our floating in a half-existence. If you wanted to demonstrate gravity in the most prototypical way, you might drop a stone, the main character’s name. And, of course, “gravity” evokes the grave, in this movie about death and coping with loss. The daughter even died of gravity. The writers could have made the cause of her death drowning, or poisoning, or a car collision, but in one of their subtler details, they tell us: she fell. She fell to earth. It is a small movie, as I say, but a grave one, and a joyful one, too, because in the end Stone chooses life and is glad that she has.

Recent comments