You are currently browsing the monthly archive for July 2017.

Joy spotted a sign for an etching workshop here in Oaxaca (grabado en metal, in Spanish): three days, five hours a day, various techniques. Investigation confirmed that the artist, Marco Velasco, would gladly teach a ten-year-old how to work with acid, something not all printmaking workshops here have been willing to do, so all three of us signed up.

The germ of this piece came to me seven years ago; it even inspired me to begin learning GNU Gimp (open-source Photoshop) because I envisioned it as a digital collage. But I didn’t learn how to make digital collages (yet), and the piece sat in my sketchbook and a corner of my mind. When I learned about the variety of marks one can make with etching, it emerged and said “make me a print!”

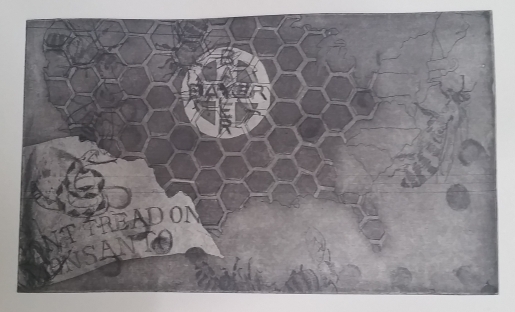

Colony Collapse Disorder, etching, about 4″ x 8″, (c) Amy Zucker Morgenstern July 2017

It involved fun research. I did not know that the headache-medicine people, Bayer, own a company called Bayer CropScience, soon to acquire Monsanto. Nor that it is one of the biggest manufacturers of neonicotinoids, the pesticides that work by attacking insects’ neurological systems, and of course an ardent advocate of the claim that they have no significant effect on bees. Nor that Monsanto has decided to protect Bayer’s flank by producing a new kind of bee. (It’s the Roundup Ready corn of the insect world. Make poison, spread it on everything, and when you discover that it kills some species you like, instead of changing the poison or ceasing to spread it, alter the species.) Bayer’s logo even resembles the cross-hairs of a rifle, a pleasing bit of serendipity. I also did not anticipate that looking up images of the Gadsden flag, the one that says “Don’t Tread on Me,” would cause websites full of US flags and pugnacious political mottos to pop up in my ads, but of course it did.

I think the founding principles that united the American colonies left us particularly vulnerable to attacks like the one on the bees (and our food sources, and the entire web of plant and animal life), but these ideas are still too abstract for art; I don’t have the image yet to express what I think is threatening to cause the collapse of the human colonies. Maybe there will be future works in a series.

I know for certain that I want to do more etching. I loved the techniques. You can scratch into the varnish that will resist the acid, or use a different kind of varnish and draw right onto it (the smudges in the lower left come from my leaning on the plate as I did that, a mistake), or scratch into the plate itself. And make areas of darker and lighter tone by how long you leave the plate in the acid, and by gently sanding the plate’s surface. Unlike relief techniques like linocut, where you think in negative (what you want to be dark, you leave behind as you carve), the marks you make on an etching plate will be dark. This makes it possible to transfer images to the plate in my own drawing style. The three days involved painting, drawing, scratching, sanding–I enjoyed every minute.

They did at least a dozen dances, standing patiently in between dances while a man told the story being acted out by the dance (and explained, every single time, that the group was from a cultural center at Teotitlan del Valle). I loved hearing the story, which was about Moctezuma and the “malos presagios” (bad omens) being told him by his advisers, as unknown people and monstrous beasts arrived on the shore. Lacking the perseverance of the children, I finally got so hungry I had to go get tamales from the food section, and missed the end of the story. I am sure it did not end well for Moctezuma. But it was very cool to hear this story of conquest, colonialization, and the culture that has withstood them, the first time I’ve heard the context for these dances.

On the way back to Tlacolula, it was raining, which solved the dust problem. The bumpy road often adds false steps to a pedometer’s reading. This one didn’t add more than a few hundred, but my Fitbit seems to think they were all taken on stairs. It reports that I climbed 43 flights.

Recent comments