You are currently browsing the category archive for the ‘books’ category.

When the news broke that another Harper Lee novel was to be released, like millions I felt excitement and trepidation. I first read To Kill a Mockingbird (TKAM) when I was twelve and have reread it every few years ever since. The characters live in my consciousness like people I have actually met. One time my sister and I were talking about the book and I said something about Miss Maudie Atkinson. “Oh, Maudie’s great,” Erika said, exactly as if we were talking about a favorite neighbor of our own. So the question of “What the hell happened to Atticus in the next twenty years?” is important and (despite internet scoffing about people’s being upset about a fictional character) anything but trivial. It’s at the core of Go Set a Watchman (GSAW) and very relevant to our lives in the United States in 2015. But it’ll be the subject of my fourth post on this book. This post is about something different.

The trepidation I felt had mostly to do with the circumstances of publication. Lee is deaf and blind now, and the communiques about this new book–actually written before TKAM and set aside–came entirely from her executor. Was someone just cashing in on an old draft that Lee never wanted to see the light? She had been asked, of course, why she’d only published one book (to which she once answered that she’d said all that she had to say); she could have had GSAW published anytime; why wasn’t it published until after she was incapacitated? It was suspicious.

As soon as I began the new book, my suspicions grew. Whole descriptions were almost identical in the two books: not the fleeting descriptions such as one expects in a series (“Harry had jet-black hair that was always untidy, bright green eyes, and a scar on his forehead in the shape of a lightning bolt”–repeat seven times), but vivid portraits such as no writer would deliberately use twice. For one of the most obvious examples, here are two portraits of Scout and Jem’s Aunt Alexandra:

To all parties present and participating in the life of the county, however, Alexandra was the last of her kind: she had river-boat, boarding-school manners; let any moral come along and she would uphold it; she was a disapprover; she was an incurable gossip.

When Aunt Alexandra went to finishing school, self-doubt could not be found in any textbook, so she knew not its meaning; she was never bored, and given the slightest chance she would exercise her royal prerogative: she would arrange, advise, caution, and warn. (Go Set a Watchman, page 28)

. . . . To all parties present and participating in the life of the county, Aunt Alexandra was one of the last of her kind: she had river-boat, boarding-school manners; let any moral come along and she would uphold it; she was born in the objective case; she was an incurable gossip. When Aunt Alexandra went to school, self-doubt could not be found in any textbook, so she knew not its meaning. She was never bored, and given the slightest chance she would exercise her royal prerogative: she would arrange, advise, caution, and warn. (To Kill a Mockingbird, Popular Library paperback edition, page 131)

The reason for the similarity is obvious: when writing her second book, To Kill a Mockingbird, Lee mined her earlier draft for some of its best passages. That makes complete sense.

Surely, then, if she decided to take GSAW out of her file cabinet 50 years later, she would read it for such repetitions and rewrite these passages. The most likely explanation for the fact that they keep appearing is that Harper Lee was not involved in the publication of this book. This is a deeply sad and disturbing fact. When people wondered whether Go Set a Watchman could possibly attain the standard set by To Kill a Mockingbird, I said I didn’t care; I would read Harper Lee’s shopping list. But damn it, only if she wanted me to. (It’s also possible that she gave the go-ahead but did not reread or edit it for publication. Given the craftswomanship she put into TKAM, I don’t give it serious credence. But who knows.)

I’ve had it happen to me: a mix-up in the editing process led to an earlier draft of an essay I wrote (this one, in fact) being included for publication. Later printings corrected the error, but I wince at the knowledge that the half-formed, awkwardly-stated thoughts that I and the editors wisely removed are out there on people’s bookshelves.

It was not easy to read Go Set a Watchman, and one reason was my growing remorse as I felt as if I were peeking into someone’s private papers. Harper Lee has given me so much, and it appears I have repaid her by reading an inferior draft that she never meant anyone to see.

Next post: Not the same Scout

My wife and daughter put their heads together for a really excellent birthday present for me: bringing our collection of Agatha Christie books to completion, including her memoirs and the so-called “romances” published under the name Mary Westmacott.

I left the latter unread for years, thinking of Harlequin romances, but they’re not romances in that sense, nor even all primarily about a romantic relationship, and when I finally picked up Absent in the Spring I was delighted. I’ve read two more since, and like Absent, they contain some of her best writing. In them she goes into all the detail of characterization that she usually skips in the mysteries. With her whodunnits, she relies heavily on types–often playing them up in order to pull the wool over our eyes, but still, there they are: the likeable rake, the bright young career woman, the buttoned-up solicitor, the taciturn retired Army officer from the far reaches of the empire, the maid named Gladys with bad adenoids and nothing much upstairs. Writing as Mary Westmacott, she delves into character with surprising subtlety. Absent in the Spring remains my favorite of these so far, as it was Christie’s; she described it as “The one book that has satisfied me completely.” The Rose and the Yew Tree stands out for its treatment of politics, an area of life that, in her mysteries, Christie usually gives a comically cursory treatment. In the spy novels, especially, you can almost hear her shrugging her shoulders (“Must give them a bad guy”) as she dashes off a description of some dastardly (and unlikely) coalition of Communists, Fascists, and international drug runners. In The Rose and the Yew Tree,she actually gets into the dynamics of a political campaign, and seems to both respect those inner workings and know what she’s talking about.

We owned almost all of the mysteries already, but many were cheap paperbacks so decrepit that the covers came away in your hand and you would occasionally get to the final pages only to discover that they’d gotten lost. Munchkin helped Joy work through the list and pulled out books that needed to be replaced. She is so pleased with her role in this drama.

Instead of presenting me with the gift, they appropriately gave me a puzzle: “Your present is hidden in plain sight in the house.” It took a few hints for me to get there (“Okay, which room?”), and then I noticed something that I was pretty sure hadn’t been there before.

“Wait, did you buy all the missing Westmacott books?” I asked. “Is that my present?”

Joy said, “It’s not so much a book as a concept . . . ,” and the penny dropped.

So now I’m enjoying reading classics I had been reluctant to pick up because the pages didn’t stay put, and marveling at her genius. Often, some minor weakness obscures the excellence of the book; rereading it reminds me just how good the book is as a whole. Yes, What Mrs. McGillicuddy Saw! relies on a Marple ex machina to extract a confession from the killer, so that the book ends on a whimper more than a bang, but the mystery keeps you guessing right up until that moment, leading us down the garden path and giving us one of Christie’s many pleasing non-recurring main characters, Lucy Eyelesbarrow. Yes, Poirot is incapable of going on vacation without stumbling over a corpse, but at least The Labors of Hercules does show that he is actually a private detective who occasionally learns about crimes from being hired to solve them. I love her short stories, and these are funny, full of twists, and completely devoid of Hastings. Hastings is such a Watson that he makes Watson look like a genius. Christie so longed to be done with the “insufferable” Poirot that she wrote the account of his death in the late ’30s, putting the resulting novel into a vault to be published posthumously (in fact it was published shortly before her death); I wish that she had given Hastings the push at the same time. It would have been a great gift to her devoted fans for us to see him die, preferably from his own thickheadedness, the same quality that inflicted so much pain on us. But again, the small weakness can make me forget, in retrospect, how great the book is. Even while I’m rolling my eyes at Hastings, his creator is doing some of her best stuff, as in Peril at End House and Lord Edgware Dies.

And as I’m reading, I’m noticing how many different ways she goes about the problem of narration, adapting it to the mystery at hand. Maybe she ditched Hastings early on (he doesn’t appear for 35 years) because, once having broken away from the tyranny of Arthur Conan Doyle, she realized she seldom needed a first-person narrator. She elevated the unreliable first-person narrator to the status of legend–anyone who thinks it’s “cheating” for the narrator to deceive the reader would be happiest staying away from Christie–but third-person narration also serves the aim of deception. In And Then There Were None, with no detective and every character very actively a suspect, being able to move from one character’s point of view to another, as third-person narration makes possible, allows her to suggest multiple red herrings (it’s also by far the best use of one of her favorite tropes, the nursery rhyme). Cat Among the Pigeons, which I recently reread, also moves quickly from one point of view to another, creating a sensation of having the magician flash a card just a bit too fast to be properly read. You know the evidence is right before your eyes, but you can’t quite see it. By the time I found out who’d dunnit, my paranoia had reached fever levels. It made the solution deeply satisfying.

And now we have them all (minus a couple of hard-to-find holdouts that the family detectives are still tracking down). Now, which one to read next . . . ?

As I drove to work today I was musing about a new installment in my very occasional series of appreciations of Ursula LeGuin. When, a little later, I saw her photo in my Facebook page, I thought, “Oh no! She’s died!” (Sorry, Ms. LeGuin. I have a morbid turn of mind.) Fortunately, she was just being cranky about Amazon, and this is not a eulogy.

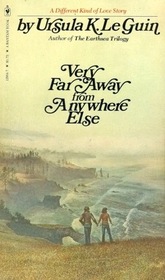

As a teenager and earlier, I read my share of teenage-problems books, about people my age dealing with such issues as divorcing parents, homosexuality and homophobia, friends who shoplift, siblings who bully, hypocritical adults, you name it. But absent from all of them was one of the problems I struggled with most: the growing realization that I cared about ideas–that I was, in short, an intellectual–and that this was not all that common. In fact, if any of the kids in these books were even interested in ideas, it must have been one of those background characters, a girl reading in the last row who didn’t even get a character description. I’m not blaming the books; they were busy with other matters, and many of them handled them beautifully. I’m just giving some background about why it was a gift and a revelation to open up one of LeGuin’s least-known novels, Very Far Away from Anywhere Else, and discover Owen and his friend Natalie.

Owen is an intell ectual. He’s not only good at math and science, but loves them. He’s not only going to go to college, a bright kid taking the expected next step; he’s looking forward to being part of a community of scientists doing experiments for the sheer passion of finding out what is true. His parents don’t understand this, and expect him to go to State, which is local, affordable, and familiar; one of the chief conflicts of the slim book is his difficulty sharing with them who he really is and what he longs for. I didn’t share that particular problem–my parents enthusiastically encouraged my intellectual explorations–but I was perfectly aware that to much of the world, and especially my peers, I was an oddball. One teacher who gathered together students who, in his words, cared about a “life of the mind,” gave me a haven, and others did too, both teachers and friends. Still. Just being offered that phrase of his, tasting it on my tongue, was like a secret pleasure hidden away from the grim hallways of high school, where we were supposed to do well in class but we were viewed with suspicion if we actually loved the life of the mind. And here was a book about loving it.

ectual. He’s not only good at math and science, but loves them. He’s not only going to go to college, a bright kid taking the expected next step; he’s looking forward to being part of a community of scientists doing experiments for the sheer passion of finding out what is true. His parents don’t understand this, and expect him to go to State, which is local, affordable, and familiar; one of the chief conflicts of the slim book is his difficulty sharing with them who he really is and what he longs for. I didn’t share that particular problem–my parents enthusiastically encouraged my intellectual explorations–but I was perfectly aware that to much of the world, and especially my peers, I was an oddball. One teacher who gathered together students who, in his words, cared about a “life of the mind,” gave me a haven, and others did too, both teachers and friends. Still. Just being offered that phrase of his, tasting it on my tongue, was like a secret pleasure hidden away from the grim hallways of high school, where we were supposed to do well in class but we were viewed with suspicion if we actually loved the life of the mind. And here was a book about loving it.

Oddballs find their own communities in time. The kid who thinks no one else loves railroad trains finds the rail club; the girl who wants to not only play the viola, but compose music for it, connects with other musicians who take her seriously. We grow up to see a world beyond our families and the 29 other people in our class, and find kindred spirits there. Sometimes, when that hasn’t happened yet and we’re confined to a world with such a small population that very few people in it seem to resemble us, we find our communities in books. This short novel assured thirteen-year-old me that somewhere out there, there were people who shared my passions. It might be very far away from anywhere else, but I’d find Owen there, and Natalie, and Ursula LeGuin herself.

(Available through my local indie bookseller, and yours)

Last Sunday, we ended the service with a ritual bridge crossing. Everyone had this image and question in their order of service–

–and I urged them to answer the question and keep that image and pledge somewhere they would see them often.

There are a couple of things I’m going to do. One is to partner deliberately with African-American-led organizations, listen to what they want me to do to help bring justice, freedom and equality to their people, and do it. The other is not so much action as the foundation for action, because when I listen to other people’s stories I am drawn into their struggles: to read a dozen books by African-Americans that would teach me something about their experience of the country we share. I decided to make it a baker’s dozen. I’ve drawn up the list now and noticed that it’s heavily tilted toward the voices of women.* So here, for Women’s History Month, are the books by African-American women that I’ll be reading over the next several months:

how I discovered poetry, Marilyn Nelson. I just learned about this book today from sister UU blogger Tina Porter, who wrote, “If I taught American History, I would make this mandatory reading. If I taught religion, I’d make this mandatory reading. If I could still make my daughters read things, I would make this mandatory reading. Because nothing could be more informative about life in America in 2015 than the story of the years 1950 to 1960 in the life of an African American girl whose father is in the military, moving the family north, south, east and west.”

Citizen, Claudia Rankine, whom I heard speaking on the PBS News Hour this afternoon and found electrifying. Must read more!

Beloved, Toni Morrison. I love Morrison, but for many years now, I have been dragging my feet about reading this, her masterpiece. I’ve endured other books about dead children; it’s time to bite the bullet.

Americanah, Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie. Adichie is actually not African-American, but Nigerian, but she spends a lot of her time in the United States and writes about the African-American experience. I wondered if anyone would give me this for Christmas. They didn’t, and the waiting list at the library continues to be long, so I’m just going to buy it for myself.

Dawn, Adulthood Rites, and Imago (Lilith’s Brood: the Xenogenesis Trilogy), Octavia Butler. My wife gave me this trilogy before she was my wife. I dipped a toe in, but couldn’t get into it. We’re going on ten years of marriage and I’ve read and enjoyed lots of other Butler, and sadly, there will be no more, so it’s back to Lilith for me. Honestly, sci fi? alluding to Lilith? How can I not love it?

Salvage the Bones, Jesmyn Ward. I don’t know anything about Ward or this book, other than it’s about Hurricane Katrina and sounds interesting.

The Warmth of Other Suns, Isabel Wilkerson. A history of the Great Migration of African-Americans to the urban north from the rural south.

Your nominations are welcome. What books–poetry, fiction, non-fiction–by African-American writers have been important to you?

*The others, by men: The Intuitionist, Colson Whitehead; The Known World, Edward P. Jones; Blues City: A Walk in Oakland, Ishmael Reed; and Brothers and Keepers, John Edgar Wideman.

During this third day of Women’s History Month I’ve been reading El Cuaderno de Maya (Maya’s Notebook), by a female writer of historic significance, Isabel Allende. My Spanish teacher was shrewd: he brought the book in one day and together we read the first few pages in the original language. It’s been the bulk of my weekly assignment ever since. I was hooked after the first paragraph, those few lines with which the author somehow evoked Maya’s personality, suggested her recent and risky history, tantalized me about her grandmother’s story, and most of all made me want to read her notebook. In English, as translated by Anne McLean, it reads:

A week ago my grandmother gave me a dry-eyed hug at the San Francisco airport and told me again that if I valued my life at all, I should not get in touch with anyone I knew until we could be sure my enemies were no longer looking for me. My Nini is paranoid, as the residents of the People’s Independent Republic of Berkeley tend to be, persecuted as they are by the government and extraterrestrials, but in my case she wasn’t exaggerating: no amount of precaution could ever be enough. She handed me a hundred-page notebook so I could keep a diary, as I did from the age of eight until I was fifteen, when my life went off the rails. “You’re going to have time to get bored, Maya. Take advantage of it to write down the monumental stupidities you’ve committed, see if you can come to grips with them,” she said. Several of my diaries are still in existence, sealed with industrial-strength adhesive tape. My grandfather kept them under lock and key in his desk for years, and now my Nini has them in a shoebox under her bed. This will be notebook number nine. My Nini believes they’ll be of use to me when I get psychoanalyzed, because they contain the keys to untie the knots of my personality; but if she’d read them, she’d know they contain a huge pile of tales tall enough to outfox Freud himself. My grandmother distrusts professionals who charge by the hour on principle, since quick results are not profitable for them. However, she makes an exception for psychiatrists, because one of them saved her from depression and from the traps of magic when she took it into her head to communicate with the dead.

Allende’s first novel, almost incredibly, was The House of the Spirits, epic in scope and powerful in its emotional and intellectual impact. From my perspective as an adoptive Northern Californian–a status she shares–her novel Daughter of Fortune is particularly interesting, because it moves from Chile to the founding of San Francisco as a modern city, during the Gold Rush. Her descriptions of modern-day Berkeley are so incisive (and funny) that although I’ve never been to Chile, I feel that Santiago, too, must be exactly as her words describe it. She has a stunning command of language, poetic yet straight-shooting, with phrases that can make you laugh out loud and shake your head in sorrow at the same time. In 2010, Allende was awarded Chile’s National Prize for Literature, one of only a few women to have received that recognition.

She was exiled from her native land in 1973 by the military coup and the assassination of Salvador Allende (her father’s cousin, or in Spanish, her tío en segundo grado). In an introduction to a memoir, she writes that the destruction of the twin towers of the World Trade Center made her a U.S. American:

I no longer feel that I am an alien in the United States. When I watched the collapse of the towers, I had a sense of having lived a nearly identical nightmare. By a blood-chilling coincidence–historic karma–the commandeered airplanes struck their U.S. targets on a Tuesday, September 11, exactly the same day of the week and month–and at almost the same time in the morning–of the 1973 military coup in Chile, a terrorist act orchestrated by the CIA against a democracy. The images of burning buildings, smoke, flames, and panic are similar in both settings. That distant Tuesday in 1973 my life was split in two; nothing was ever again the same; I lost a country. That fateful Tuesday in 2001 was also a decisive moment; nothing will ever again be the same, and I gained a country. (“A Few Words of Introduction,” My Invented Country, translated by Margaret Sayers Peden)

Not having yet read the book, I don’t know why the ironic twinning of these tragedies led to her feeling that she had gained a country. How does one even make a home in the country that destroyed one’s homeland, much less proudly claim that new nationality as one’s identity? If anyone can trace the complexities of that journey in such as way as to bring us along and make us understand, it’s Isabel Allende.

(An earlier version of this post stated incorrectly that the English translation of El Cuaderno de Maya was by Allende herself, and omitted the names of the translators of both books quoted.)

I can’t stand roller coasters, but I guess I have a similar craving for experiencing fear and suffering from a safe position, because I have been reading books that make me writhe with anxiety. Right now I’m reading The Woman in White, by Wilkie Collins. The only people in danger are creations of Collins’s imagination, but I’m gripping my seat and occasionally yelping “Oh no!” and “Don’t do that!”

Is this bad for my blood pressure, do you think, or is vicarious terror good for us?

I’m reading The Fault in Our Stars, and aside from loving it, I am deeply satisfied that the narrator calls Maslow’s hierarchy of needs “utter horseshit.” I have always thought so, at least if Maslow said what my teachers said he said: that you can’t be concerned with the needs on the top of the pyramid until you’ve satisfied the needs lower down. In fact, the same school that taught me that taught me about the kamikazes, who are an excellent disproof.

But you don’t need to take sophomore-year history to have observed that people who don’t even have shelter or safety still do art and philosophy and concern themselves with self-actualization.

A brief prayer from The Left Hand of Darkness comes to me often. On the planet Gethen, in the book, it’s from the Handdara; here on Earth, it sounds like something from process theology. I was moved to say it by today’s photo on NASA’s Astronomy Picture of the Day:

“Praise Creation unfinished!”

I keep wanting to write about the work of Ursula K. LeGuin, and am intimidated by the number and variety of things I want to say, and frankly by the depth of emotion involved. So I’m just going to write a little chunk at a time.

LeGuin wrote the only Taoist novel I know of, The Lathe of Heaven. (I hope if you know others, you’ll name them in the comments.) Taoism arises in The Left Hand of Darkness, also–most explicitly in the scene from which the title is taken, when Genly draws a yin/yang for Estraven, and Estraven shares a poem from the Handdara tradition, a paradox-drenched religion she creates for the novel:

Light is the left hand of darkness

and darkness the right hand of light.

Two are one, life and death, lying

together like lovers in kemmer,

like hands joined together,

like the end and the way.

More broadly, the complex balance, the dance of dualities, that is of such concern to the Taoist sages is clearly one of LeGuin’s abiding concerns as well; we see it in work from Earthsea to Searoad. Still, The Lathe of Heaven engages the question most directly, not because it quotes liberally from Taoist sources (though it does, including in the title), but because it looks at it ethically: when should we act and when should we refrain from action? If you could change the world with a wave of a wand, or in her protagonist’s case, with a few minutes of dreaming, would you? Or would it depend–and in that case, on what? Are we really supposed to live by Lao-Tzu’s teaching, “The Sage occupies himself with inaction”–is that the height of moral responsibility or the abdication of it?

George Orr has dreams that change reality, retroactively and invisibly to anyone except him. He dreams that his aunt dies in a car crash and when he wakes, she has died in a car crash. The awesome power and, to his mind, responsibility, of his dreaming self are tormenting him, so he seeks the help of Dr. Haber, a psychiatrist who specializes in dreams. Once Haber begins to believe George’s claims, he starts suggesting improvements to the world that George then makes, unwillingly, while asleep.

George Orr has dreams that change reality, retroactively and invisibly to anyone except him. He dreams that his aunt dies in a car crash and when he wakes, she has died in a car crash. The awesome power and, to his mind, responsibility, of his dreaming self are tormenting him, so he seeks the help of Dr. Haber, a psychiatrist who specializes in dreams. Once Haber begins to believe George’s claims, he starts suggesting improvements to the world that George then makes, unwillingly, while asleep.

PBS made a movie of the novel, a rather low-budget affair, as PBS movies generally are. Given the spending constraints they were under, they did an admirable job, and there’s excellent acting, but one thing the adapters got badly wrong, in my view, was the character of Dr. Haber. They turned him into an evil scientist, but he’s not. He’s a humanitarian; he wants to use George’s power to end hunger, poverty, and racism. His noble motives are all mixed up with base ones–he gets himself promoted in dream after dream, until he has risen from unknown Portland shrink to special advisor to the world government–but that’s not the main reason he goes wrong. He goes wrong because he utterly lacks awareness of himself and, most of all, a sense of connection to anyone or anything outside himself. To him, dreams are just a tool to manipulate reality, whereas to George they’re a seamless part of the whole, as are (in some fashion) the ills he’s redressing, and as is George himself. Haber is about as far from the ideal of the Taoist master as you can get: at one point George privately observes that the psychiatrist seems not to know the uses of silence, and it’s just as clear that he doesn’t know the uses of inaction.

Making him a bad guy misses a very deep point of the novel, about how our best intentions go awry if we live in the illusory belief that we are separable from the interdependent web of all things. It’s easy to fall into that illusion. I can even see myself, potentially, in Haber: the do-gooder gone off the rails. What’s the solution? Not to refrain from doing good, certainly. That would be nihilistic. Nor to use every tool at our disposal to fix the world. We need a certain kind of harmony that “Mr. Either Or,” the somewhat passive, somewhat uncertain and indefinite, hero has, and that his dynamic doctor lacks. How to find that harmony seems to be the key. I can’t state the key in one sentence, or even sum it up to myself, but when I read Chuang-Tzu, or Lao-Tzu, or The Lathe of Heaven, I start to feel as if it really exists.

I have just read The Night Circus, by Erin Morgenstern (no relation). Very few books have created a place that I longed to be able to go to in real life. I have wished Hogwarts were real, and that I could slip through the ivy-covered door into the Secret Garden; and now, oh how I wish the Cirque des Rêves were really touring around the world, bringing its exquisite magic to us. I would be a Rêveur, one of the people who follows it around, a beauty groupie. I would knit a Rêveur’s crimson scarf for me, and one for Joy, and we would go into the Cloud Maze tent, and the Ice Garden, and the Hall of Mirrors, and see the illusionist work impossibilities, and take in the intricacies of the clock, and wander through tents where everything is made of paper and covered in words. I don’t know if the Munchkin would need to come along (though she would enjoy Widget and Poppet’s acrobatic kittens). She already seems to live in a magical world.

But then, according to the author, we all do.

“Is magic not enough to live for?” Widget asks.

“Magic,” the man in the grey suit repeats, turning the word into a laugh. “This is not magic. This is the way the world is, only very few people take the time to stop and note it. Look around you,” he says, waving a hand at the surrounding tables. “Not a one of them even has an inkling of the things that are possible in this world, and what’s worse is that none of them would listen if you attempted to enlighten them. They want to believe that magic is nothing but clever deception, because to think it real would keep them up at night, afraid of their own existence.”

Or as Stan Shunpike, conductor of the Knight Bus, says when Harry Potter asks him why the Muggles don’t hear the bus,

“Them!” [said Stan contemptuously.] “Don’ listen properly, do they? Don’ look properly either. Never notice nuffink, they don’.”

“But,” Widget says, “some people can be enlightened.”

Recent comments