You are currently browsing the monthly archive for May 2023.

I learned as a child in an observant Jewish family that the most important holidays in Judaism are:

- Shabbat, celebrated every week;

- the High Holy Days: Rosh Hashanah and Yom Kippur, which are ten days apart in the fall;

- and the three agricultural festivals: Passover, Sukkot, and Shavuot.

Ah, Shavuot. Least-known and most boring of the major holidays. Far outstripped by its trivial younger siblings, Purim and, of course, Hanukah (as are most of the others). I always liked Shavuot, as a kid–I liked all of the holidays–but it caused me a little trouble. Like the other five of the above Big Six, and unlike Hanukah or Purim, it requires strict observance: in my family, no writing, travel except by one’s own power, or spending money. And you go to shul during the day. Mix those facts with people’s ignorance of its existence, and you get this exchange:

Student: I’ll won’t be here on Wednesday and Thursday. It’s a Jewish holiday.

Teacher: Another one?!

To be fair to the schools, I think this exchange took place only in my head, or between me and friends. The teachers were very professional and respectful of our civil rights. And I was a good student and kept up with my work despite the two-day embargo on writing. Oh, that’s another thing that makes Shavuot an odd one out. Unlike its triplets, Passover and Sukkot, which are a week long each*, it only gets two days (in fact, I started this on the first day of Shavuot, Sunday’s busyness intervened, and now I’m posting just in time for the end of the holiday). What the heck?

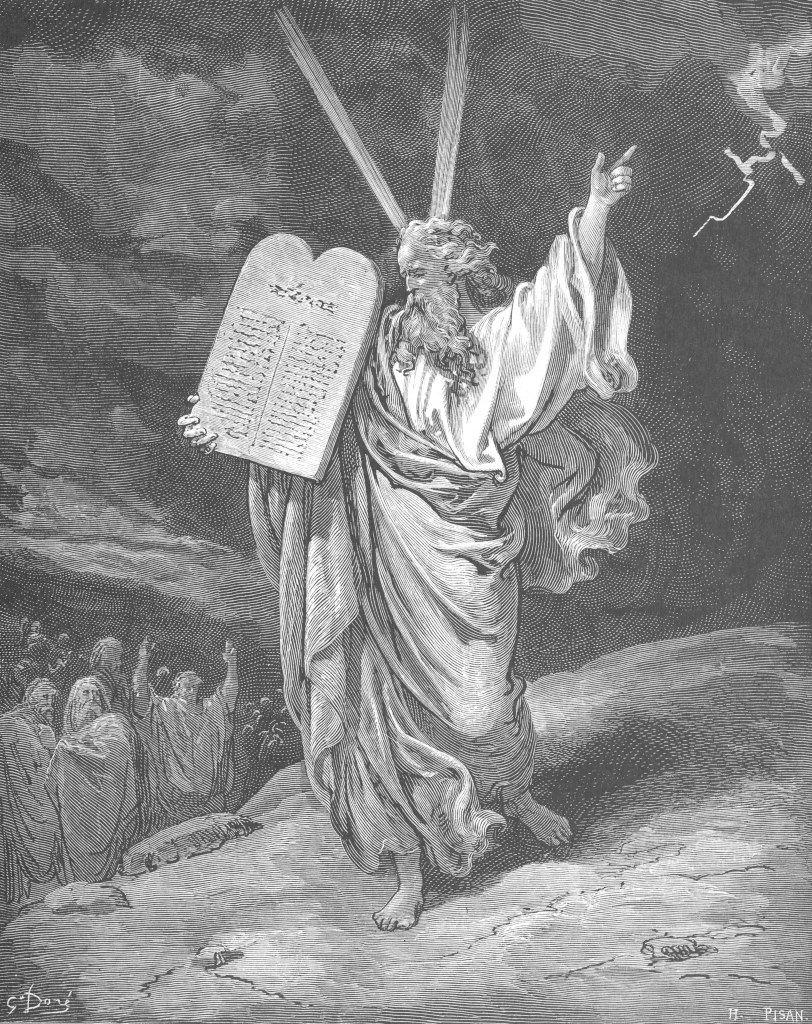

All right, so what is Shavuot? It celebrates the receiving of the Torah from God at Mt. Sinai. By tradition, this took place seven weeks and one day after the Israelites’ escape from Egypt. By way of celebration, one eats milchig, dairy–in the United States, blintzes are traditional, as is cheesecake for those who like that sort of thing (I do not)–and in the services, the central scripture is the book of Ruth. It’s a story of harvest, and also of refugees, so it’s a lovely fit.

Some questions I either never asked, or don’t remember the answers to:

- Tradition says Moses was up on Sinai for 40 days. But the people received the Torah 50 days after leaving slavery. So did the people take ten days to get to Sinai, and then receive the law after 40 more? Or did they take 50 days to get to Sinai, and didn’t actually receive the law until day 90? Ten days seems like a pretty quick trip; I don’t know precisely where they fled from, but Google Maps tells me it’s a walk of 3 1/2 days from Cairo to Mt. Sinai. Make it an entire people, including very old people, sick people, and small children, and maybe bringing some goats and such, and ten days seems unlikely. But if it took them 50 days to get there, first of all, that’s a really long time for a short distance, and second, it makes 50 days a strange interval to choose between Passover and Shavuot, since day 50 wasn’t when they got the Torah, but when they started waiting impatiently for Moses’s trip up and down the mountain to be completed. I could probably find out a lot more just by reading these chapters of Exodus, but I think I’ll just raise the question and let someone else research the answer.

- “The receiving of the Torah” is very confusing because, well, by the time Shavuot comes around, we’ve been reading the Torah, the Five Books of Moses, from the beginning since fall, and it has been mostly history. Did God give Moses the story of the Garden of Eden? I realize as I write this that what our teachers meant by “God gave us the Torah” was “God gave us the law,” which is a smallish part of the Five Books. The rest of the Torah is the story leading up to, and following, the revelation at Sinai.

- Also, there’s that whole Moses bringing down the two tablets thing. I had this vague sense that Moses brought down the Ten Commandments and that was it. Again on reflection, it’s clear that the images of Moses bearing the tablets are a visual metaphor for his bearing the entire Law in his mind.

- Why dairy, anyway? There are various theories, none very convincing. I always kind of figured it was just to give dairy a boost. Usually, holiday meals are fleishig, meat meals, I suppose because meat is expensive and appropriate for special occasions. Ours almost always featured chicken or, at Hanukah, brisket. Since observant Jews can have either one of these items or dairy desserts (you can’t eat milk for some hours after eating meat, nor meat for at least half an hour after eating dairy), this means you never do end up having cheesecake for dessert, nor cheese blintzes as an appetizer. So Shavuot is their moment. Or maybe, as in the joke about the Pope and the Wonder account, there was some lobbying from the dairy producers of the Jewish world.

- I still don’t know why only two days, instead of a week.

- And the biggest question, which I know I did ask as a child, but if I got a satisfactory answer, I have no memory of it: since this is the anniversary of receiving the Torah, why isn’t it the day to celebrate the same? Shavuot is celebrated in Sivan (June-ish; the Jewish calendar is lunar and so it doesn’t always line up with the Gregorian calendar). Why is Simchat Torah, the day of Rejoicing in the Torah (and one of my favorite holidays in my devout days), attached to Sukkot way back in Tishrei (October-ish), instead of to Shavuot?

So it turns out that little Shavuot packs a lot of questions. Whether you have any answers to them or not, if you celebrate Shavuot, I hope it has been a happy one and that you enjoyed every bite of your milchig meal.

*Though only the beginning and end of the week have strict rules. The days in between, Chol Hamoed, are pretty much like any weekday, except that in the case of Passover, of course, bread and grains are still off the menu.

Recent comments