You are currently browsing the daily archive for July 14, 2024.

Mystery writers often have series with recurring characters, and we can well understand why. They can develop a character over many books of their career and many years of the character’s life; their readership builds a rapport with the character and is likely to snatch up the next volume when it is published; they themselves don’t have to develop a cast of characters from scratch with each book, but have at least a core figure or two all ready to go.

But the recurring character presents a realism problem. How can they account for the fact that crime happens whenever this person is about? Well, the easiest way is to make the person a private detective, a police officer, a coroner, or someone else who is presented with corpses on a regular basis, oftentimes as a result of apparent foul play. Thus they avoid the “Mayhem Parva” syndrome, as the mystery writer Robert Barnard affectionately called it (“Parva” is like “-port” or “-minster,” frequently attached to place names in the British Isles). He was a big fan of Agatha Christie, but all Christie fans know that you’d better stay away from St. Mary Mead if you value your life. For such a charming, small village, it has a hell of a murder rate, and the fact that Miss Jane Marple is there to solve the crime will be of little comfort to you and your grieving relatives. Maybe that’s why Christie wrote so few Marple mysteries: only 14 novels and 20 short stories (okay, “only” is a relative term, applicable in this case because Christie wrote 66 mystery novels and 15 collections of mystery stories in total). Miss Marple isn’t a detective; she’s just an exceedingly shrewd old lady with no illusions about human nature, her knowledge of which has been honed through decades of observant, gossipy village life.

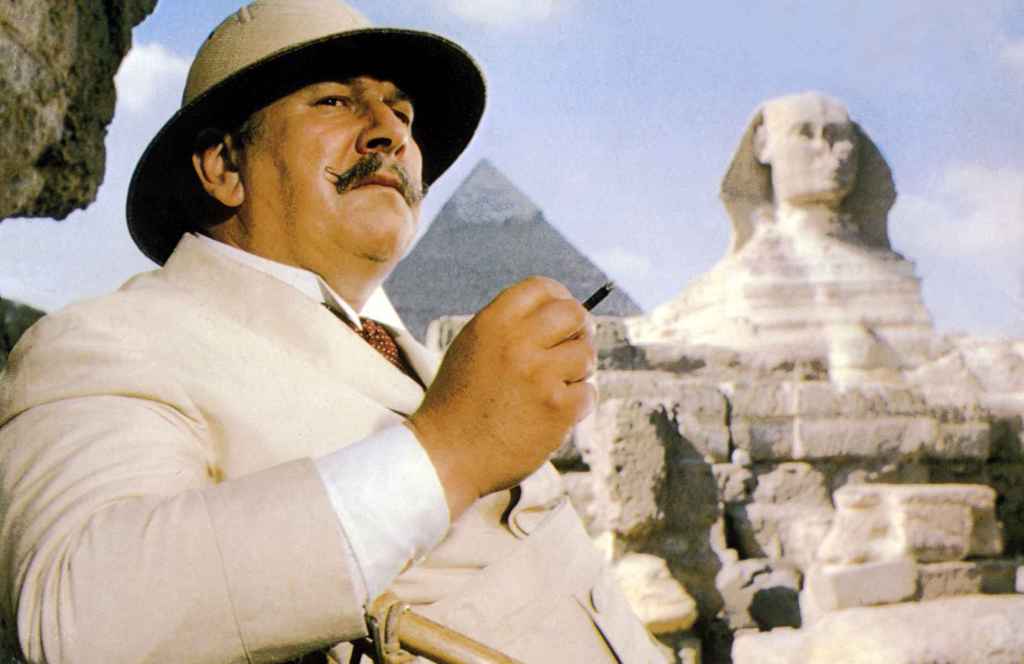

Christie wrote far more featuring the private detective Hercule Poirot–30-plus novels and over 50 stories or novellas–even though she described him as “insufferable” and “a creep” and even (spoiler alert) killed him off in a book she wrote about 20 years into her career. She put it away in a vault and didn’t submit it for publishing until shortly before she died, writing dozens more Poirot mysteries in between. Maybe, as she said, she thought she had an obligation to keep giving the public a character they adored; maybe she just couldn’t hack the kind of pressure that Arthur Conan Doyle came under when he drop-kicked Sherlock Holmes over the Reichenbach Falls, and knew that like Doyle, she’d end up bringing her detective back from the dead. However irritating his author found him, Poirot could encounter dozens of mysteries without stretching the credulity of readers, because solving mysteries was his job, and people brought him cases.

Except that that isn’t how most* of his cases come his way. Sure, people bring him mysteries to solve, as in Dumb Witness, Mrs. McGinty’s Dead, and Cat Among the Pigeons, but look at how many times a murder just happens to happen when he’s around:

The Murder of Roger Ackroyd

Death on the Nile

Murder on the Orient Express

One, Two, Buckle My Shoe

Peril at End House

Evil Under the Sun

Death in the Air

The Hollow

Murder in Mesopotamia

The Mystery of the Blue Train

I could go on. In fact, St. Mary Mead is an oasis of peace compared to the immediate surroundings of wherever Hercule Poirot happens to be. If you see his name on an airplane manifest or in the guest book of a hotel where you’re about to check in, change your plans. The man is a wrecking ball.

What is even the point of making your detective a professional detective if he mostly finds his mysteries by being in the wrong place–well, no, let’s say the right place at the right time? I think the origin of this amusing murder streak is that Christie really loved to write about places far away from London or (her other most common setting close to home) the southwest of England. In my opinion, some of her best writing comes into play when she describes locales in the Middle East, where she often accompanied her archaeologist husband, Max Mallowan. Her descriptions of English villages are desultory, almost lazy; they practically shout “Oh, you know what it looks like, post office, vicarage, tidy gardens, now let’s get to the plot”–but put her in a souk in Baghdad or at tourist stops along the Nile, and she turns out to have a gift for description. (I ought to go find a couple of examples and type them in, but I’m too lazy to do it. Read Appointment with Death, They Came to Baghdad, Death on the Nile, etc., and you’ll see what I mean, and you’ll have a great time too.) For this or whatever other reasons, she didn’t want to leave Poirot in London. She sent him abroad, and disaster followed in his wake.

*I am not quite obsessive enough to count them all up, so it’s possible that more than 50% of Poirot’s cases are, in fact, cases brought to him by clients. Feel free to out-obsess me.

Recent comments